I’m a fat, financially precarious middle aged non binary lesbian: a textbook example of how the intersection between different kinds of oppression works. Things don’t simply add up, but there is an exponential factor at work. I can say without a doubt that in my experience being fat is way worse than being queer. I’ve been fat all my life, I’ve faced the profound hatred and disgust our society feels for fatness, and the first little changes are happening just now. At the same time I have also seen the intense positive changes in the way the queer community is treated. In many parts of the world discrimination against queer people is seen as reprehensible, without an excuse. I am grateful and glad that there are so many resources and spaces available to combat queer oppression. I have created quite a few of them myself. However, there are very few people undertaking the journey to deconstruct the stigma around fatness. This is because our society still rewards fatphobia, both at a symbolic level and in terms of material living conditions. Being fat is seen as a moral failure or the breaking of some unspoken shared social values. Fatphobia is so systemic, deeply rooted, and pervasive that we often don’t notice it’s there. It is part of us and how we measure our worth. And all of this happens even if science knows very well that 95% of diets are deemed to fail and it’s not the dieters’ fault1, mainstream storytelling notwithstanding. Fatphobia condemns women, people socialized as women, increasingly men, and people of other genders to widespread unhappiness and contempt completely independent of their own actual weight. Even people considered to be a normal weight worry because they still see

themselves as fat and therefore ugly, not fitting in with unattainable mainstream aesthetic standards. What these folks don’t understand is that fatness is not a feeling but an objective condition that implies a frequent experience of the stigma. When fat women and people socialized as women report sexual assault, they are believed even less than non-fat women because of an implicit belief that fatness is so disgusting, it makes you unrapeable.2 Who would want to screw you, fatty? Minds clouded by fatphobia don’t take into account that the key element of assault is power—not erotic desire. Fat people also have a harder time finding work, especially public-facing work, because people don’t want a fat person to represent their business.3 Fat people often stop going to the doctor because every ailment is typically attributed to their fatness, regardless of what their symptoms are and the fact that body fat itself isn’t even the cause of the illness.4 Or, when they do go to the doctor, they get a late or incorrect diagnosis that actually puts them at medical risk. In countries without public healthcare, like the United States, health insurance for fat people can cost a lot more, because they are considered to be at higher risk. Fat people are generally considered to be lazy and lacking willpower because our own body is seen as a sign of our inability to resist impulses. In addition to these structural discriminations, fat people are the target of daily microaggressions from parents, friends and partners, as well as insults from strangers in the street or online. If it even needs to be said, fat kids and teenagers are much more likely to be bullied by their classmates and sometimes even teachers.5 I can testify that queer spaces always declare to be extra inclusive and that “diversity is a value,” but the reality is that queer communities have often assumed the same prejudices of the straight world, not being real safe spaces for non-conforming bodies. So I’m very happy that intersectionality has been very hype in the last years, because for the first time ever I feel seen – at least a little – by my same community. Canadian sociologist Erving Goffman teaches us in his classic work Stigma (1963) that one of the potential reactions of stigmatized individuals is to accept being on the borders of societal systems and in return to meet similar people who can help them get by in a hostile societal system. Of course these marginalized people are going to share the same set of countercultural values. This is the underlying impetus for the activism and community of many oppressed groups, and fat people are no exception. As usual with oppressed groups of people, fat persons included, those that tend to emerge as leaders are white, cisgender, and privileged, generally inhabiting bodies that are not considered at the extremes of the scales. This has been made worse with the rise of self-marketing and social media algorithms governing a significant part of our lives. The very concept of body positivity was hijacked by people whose message is essentially “I’m fat, but not very. And I eat well, I exercise. It’s not my fault. Love me.” These “activists” concentrate on the individual aspect of body positivity but ignore the structural realities of fat stigma. If all of society is constantly telling you how disgusting you are, it’s impossible to love yourself all the time. Positivity at all costs is toxic. We must not feel guilty if some days we disgust ourselves, or we don’t feel comfortable showing even a bit of our body in public. Self-love must not become the most important obligation, the most frequent social performance. It is not all about self, it is also about community. We must not only look inward for internal acceptance. We must face outward and change the systems of oppression that make us hate ourselves to begin with. The reason why people are fat is not important. We are always owed what I call “the bare minimum of human decency,” always and in any case. There are no magic recipes for living happily as fat people, but it is possible to create more peaceful paths for ourselves through deconstructing stigma. Something that I found very liberating was coming out as a fat person, the same way I came out as queer. The same with my queerness, I acknowledged that fatness is a fixed component of my identity, as opposed to a negative phase that will pass. This helped me find community. It also helped me to relax and enjoy activities that usually fat people avoid: dancing, going to the beach, dressing however you like, playing frisbee in the park, flirting with someone. I was flabbergasted when I found out that Kathleen LeBesco highlights this strong parallelism between fatness and queerness in her book Revolting Bodies? The Struggle to Redefine Fat Identity (2004). She points out that a coming out narrative about queerness has developed, and we can observe it in movies and books, while at the moment we still don’t have any coming out narrative about fatness. It doesn’t matter if we move forward in our lives with small steps or complete and sudden transformations. What is absolutely crucial is that we begin casting aside all of these structures, to begin feeling a little happier with ourselves and in the long run to change the structures of oppression that create and perpetuate fatphobia.

- 1 ”Why diets don’t actually work, according to a researcher who has studied them for decades”. Roberto A. Ferdman, Washington Post, Online. May 14, 2015

- 2 “Tipping the Scales: Effects of Gender, Rape Myth Acceptance, and Anti-Fat Attitudes on Judgments of Sexual Coercion Scenarios.” Alexandra M. Zidenberg, Brandon Sparks, Leigh Harkins, Sara K Lidstone. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 2021 Oct; 36 (19-20).

- 3 “Fat People Earn Less And Have A Harder Time Finding Work.” Ronald Alsop. BBC. Online. Dec 1, 2016.

- 4 “Addressing Medicine’s Bias Against Patients Who Are Overweight.” Rita Rubin. JAMA. Feb 20, 2019.

- 5 “BULLYING, Bullycide and Childhood Obesity,” JoAnn Stevelos, MS, MPH. Obesity Action Coalition (OAC), 2011.

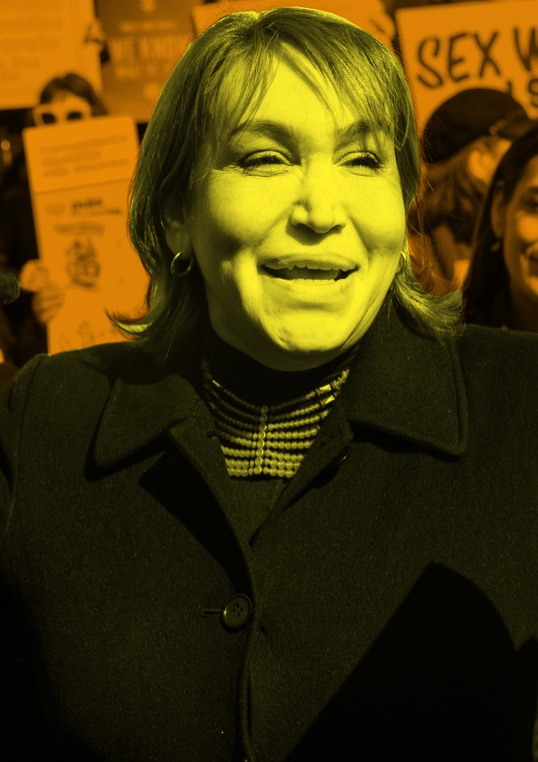

Assa Traoré is a rallying voice in the movement for Black lives in France, a country where young Black and Arab men are 20 times as likely as white men to be stopped by police.1 In 2016 her brother Adama Traoré was killed in police custody after being frisked on a bike ride home. His last words were “I can’t breathe.” Forging a personal tragedy into a national movement, Assa immediately quit her job and founded the Committee for Justice and Truth for Adama. She has spent the last six years fighting for justice for her brother and against systemic racism in France and is a constant presence at marches for racial justice. Below, Assa speaks to CHIME about the leadership of Black women in protest movements; the importance of justice for all, not for some; and what she thinks of the term ‘white privilege.’

CHIME: Women and femme people have long been the leaders of anti-racist movements. From Angela Davis, to the founders of the Black Lives Matter movement, to the Mothers of the Movement in America, and now you. Could you speak to why women have played such an outsize role in anti-racist movements?

ASSA TRAORÉ: I’ll answer this question in a rather colonial way: men of color have always been denied a voice because they are not considered as being able to participate in the construction of the country and the world in which they live, while women of color have always had a place in the fantasy of colonists. Men were considered harmful to society. Most often, the men were the ones that were sent away or killed. It was the women who remained and the women who carried the torch and fought for change. Let me tell you the story of my little brother, Adama. In France, Adama was not considered capable of participating in the construction of this country and this world because he was a Black man from a lower-income neighborhood. He was repeatedly stopped and searched on the street, he was not seen as someone who could enact positive change in this society. It’s important to understand that Black men from low-income neighborhoods like him will have a finger pointed at them from a young age – by the justice system, the police, the arrests, racial profiling – and it is going to define their whole life. This “finger” is going to guide their choices, their educational and professional career, where they’re going to live, the areas where they’re going to spend their time. And it’s going to be very complicated, very difficult to fight this “finger”—to fight this system. There’s no place for them, so they are totally dehumanized, which is not necessarily the case for women.

CHIME: We had a special issue of the zine about the #SayHerName movement, which was guest edited by Kimberlé Crenshaw. Professor Crenshaw is known for coining the term ‘intersectionality,’ meaning that Black women are subject to discrimination on the basis of both race and gender, and a combination of the two. I was wondering if you could speak to that a little bit, and what role intersectionality plays in the movement you are spearheading in France.

ASSA TRAORÉ: Let me give you some very concrete examples. I am being attacked by the far-right, by representatives of the state. I am constantly harassed on social media. I receive rape threats. I receive death threats. On social networks, I am regularly compared to an animal and criticized as a woman and a Black woman. In fact, if I wasn’t called Assa Traoré, if I was a white woman, well, my efforts would have been seen as a just and noble cause. That means that for them, it’s not normal for a woman—and a Black woman—to stand up for a Black man: that’s too much “Black.” It’s also important to say that men oppress other men, that men who are discriminated against are also oppressed by other men. So yes, it’s a constant set up. But in reality, it doesn’t affect me. I am a victim but I refuse to be their victim. I just forge ahead and let it roll off my back. For me, their words have no consequences. The violence has escalated to physical violence – I have been attacked on the streets. This violence must be confronted head-on. So yes, the fact that I’m Black and the fact that I’m a woman are both very, very important factors. We have some white women who call themselves feminists, who will stand up as soon as a white woman is attacked, as soon as a comment is made; but as soon as it involves a Black, Arab, or other woman of color, these women who call themselves feminists or whatever, will not speak up. As if it is legitimate for a Black woman, or any other woman of color, to be attacked. So, it’s very hypocritical.

CHIME: On the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall riots, you made some really powerful statements about the queer community and its involvement in Black liberation. You said, “Why do we have strength today? Because the Adama fight is a fight that we let everyone take ownership of, I don’t think people from the queer/LGBT community have ever felt a look of discrimination or contempt in our marches. We intentionally make it a safe space.” Could you speak to the role of the queer community and particularly about the epidemic of violence against Black trans women?

ASSA TRAORÉ: With the Adama committee, I started from the principle that if I demand truth and justice for my brother then I can’t say “I want us to live in a world where there is equality, where it is fair,” while others are suffering injustice. This isn’t possible. This means that if we demand justice for Adama, all forms of injustice must be denounced. If all forms of injustice are denounced, then I can say: “We want to live in a country where there is equality, where we are all equal.” What bothers me is when people defend their own little cause, while someone else has been killed because of discrimination. How can we live in a just world if one suffers and the other takes what there is to take? It would be a bit like copying what the system does. With the Adama committee, we decided to go to all the protests, to form alliances and build solidarity. When we say build solidarity, we’re talking about the LGBT community, the cleaning ladies, the students, the gilet jaunes, but really everyone... All the neighborhoods.The message that I’m conveying and that I want to convey, which works and which worked in the Adama committee, is that the fight belongs to everyone, no matter where you come from, who you are, no matter your religion, your beliefs or lack thereof, or your sexuality. Today, you cannot live in a country if anyone, any human being, suffers an injustice. Every person must be defended.

CHIME: In a piece in The New Yorker, you said that you object to the phrase “white privilege,” saying, “If I say white privilege, I accept that white people are above me. There is no white privilege. There are human lives.” Could you explain that a little bit?

ASSA TRAORÉ: I don’t like this term, which became popular after George Floyd’s death. It was used a lot. I don’t like the word “white privilege.” In fact, we’re fighting for equality, not for Black privilege. For me, when we use this term, it means that we believe Black people are still inferior and white people are above them. It’s saying: “Yes, I’m using white privilege to go and save a Black person.” We’re still in the situation of the white man coming to save a Black man. This is a mold that must absolutely be broken. The white man must no longer play the role of the savior who rescues the Black man. On the contrary, for me, white people should fight and say “We don’t want this term to be used, we don’t want there to be white privilege. We want there to be equal and human privilege for everyone.” When we’re fighting to denounce discrimination, when we’re fighting for equality, it’s to say that we don’t want there to be any privileges anymore, but that there should be equal privileges, that my privileges should be equal to those of a white person, an Asian person, a person from the LGBT community, a vegan person. It doesn’t matter. If my brother had been considered equal to any other human being, my brother would not have died that day. And when we talk about white privilege over a man, it means that we still have an advantage over that man. It means that there is a dehumanization somewhere, which is not balanced. It’s humanization that has to come first. For example, if there had been humanization when George Floyd was about to die, if those policemen had even an ounce of humanity, they wouldn’t have killed him, they wouldn’t have killed my brother.

CHIME: In this same New Yorker piece you say that, “I want to say that [racism is] even worse in France. People will talk about social violence. They’ll never talk about racial violence, contrary to the United States, but it’s there.” Can you elaborate on that?

ASSA TRAORÉ: The question is not “is France more violent than the U.S.?” because it’s not that it’s more violent, it’s that the right wing in France always says that it’s worse in the United States. In fact they use this argument to say, “You’re doing too much. Stop talking. Just because a Black person was killed or an Arab person, it doesn’t mean that you have to talk about it.” When, in fact, the question that needs to be asked is: Why does France not recognize that there is police violence, discrimination, and racism in France? There is. There has been since colonization of Africa and the Middle East. The French police was built on the back of a racist state, on violence where Arabs were thrown in the Seine river, and it has never been addressed. When my brother Adama Traoré died, France spoke much more easily about what was happening in the United States and pretended that nothing was happening in France while my brother died in exactly the same way as George Floyd, suffered exactly the same violence. Today, here we are, six years later. There’s a total denial of justice, where we have a justice system here that protects the police. Yes, there’s violence. In fact, for Americans reading this article, they should understand that Paris is not just the Eiffel Tower, fashion, the Champs Elysées... When the curtain is pulled back, there is extreme violence. In fact, France is not going to talk about what’s happening here, but rather about what is happening abroad. That’s why it’s so important that I’m on the front page of the Times and The New Yorker. Let the outside world see: “Oh, something extremely violent is happening in France,” so that people can understand that we’re living in a violent situation. I ask for truth and justice for my brother, and many think what I’m asking for is not normal.

CHIME: Is there anything else you would like to add?

ASSA TRAORÉ: Today, we can’t demand justice and still be a spectator of another person’s injustice, no matter where they come from or who they are. And that’s important. And I think that today all our struggles must be intertwined, we must create solidarity. In fact, we must make the word “solidarity” big and bold everywhere. And when we create solidarity, we create connections, we create feelings, and we create attachments that make people want to help others, and that’s important. It’s important that through your zine, we can discover and we can understand that there are battles being waged here in France for the whole world to see, because they must all be fought together.

- 1“How Assa Traoré Became the Face of France’s Movement for Racial Justice.” Vivenne Walt. TIME. December 11, 2020.

In Imagined Communities (1983), the late Southeast Asian researcher Benedict Anderson (1936-2015) proposed the idea of “print capitalism” to explain the imagined communities that arose in 18th century Europe. Printed forms like novels and newspapers reproduced imagined “national” communities; put another way, print capitalism enabled people to think about themselves and connect with others through profound new mediums. When I started collecting queer archival material from across Asia, I found that before the 1980s, queer Asian subjects also drew from mainstream newspaper coverage to imagine themselves and the existence of others like them. But what mainstream newspapers and novels of that time created was not community, but division. Reportage that pathologized, criminalized, and sexualized queerness caused queer subjects to be excluded from society, forcing them to hide themselves. But in the late 1980s—when politics became more democratized, urban consumption flourished, and individualism gradually developed—”print utopias,” written in the voices of queer people themselves, began to appear. “Ruin” is the only full-time employee and one of the founders of Queerarch (Queer + Archive), a South Korean queer archive. According to Ruin, while Queerarch was established in 2009, the construction of the archive dates back to 1998. At that time, Ruin and Hahn Chae-yoon founded the publication Buddy (1998-2003) and later established the Korean Sexual Minority Culture & Rights Center (KSCRC), a jointly facilitated magazine publisher and activist organization. These initiatives became an important foundation for Queerarch, enabling the archive to develop in tandem with post-1990 Korean queer history. Queer archives and corresponding art exhibitions all raised the following core questions: How can we challenge the narrow (art) historical view of South Korea? How can we resist the discursive and academic violence that has resulted in the historical erasure of queer lives? Necessarily, each set of works traced the footsteps and life experiences of queer “predecessors” through historical materials. At the same time, these pieces gave

meaning to the “forgotten” and the “silent.” These creative interventions in the past pointed towards the imagination and connective potential of future generations. Queerarch’s archival methods are mainly based on “collection and recording,” and its scope includes “records related to sexual minority groups and queer people.” The archive specifically includes books; magazines; newspaper articles; university club and group directories; research papers; meeting minutes; personal diaries; web videos; audiovisual materials; event photos and promotional posters; badges; and other objects, including journals from the U.S., the Netherlands, Taiwan, Uganda, the UK, and Japan. Based on the way the online archive is organized, these materials are largely divided into “themes” (AIDS,refugees/immigrants, bisexuality, youth, etc.); “record type” (photography, books, personal records, objects, printed matter, etc.); “language and region;” “source” (collected by activist organizations such as KSCRC, or donated by individuals); the “Queer Cultural Festival,” and other “cultural festivals of various regions” (those of Daegu, Busan, Jeju, and foreign countries); and “events” (Choi Hyun-sook coming out of the closet to run for a parliamentary seat in 2008, the 2014 Seoul Charter ofHuman Rights controversy, the PyeongChang Pride House, and so forth).1 Of particular note among the 8,000-plus archived materials is a scrapbook numbered PL-00000014. This scrapbook was created in 1995 by a transgender woman who personally donated it to the Buddy office in 1998. When the scrapbook arrived at the Buddy office, the cover was mottled and torn, showing traces of its owner’s physicality. Its contents present a personal testimony of hardship, self-hatred, and occasional hope. The scrapbook also includes pieces of artwork, most of which are self-portraits and illustrations of the body the writer longed to inhabit. 2These kinds of archival documents would not only be included in Queerarch, but would also become key materials for the 2019 art exhibition twenty years later. This archive is in every way a reflection of queer studies scholar Sara Ahmed’s assertion that the hidden queer life—and illegible queer experiences—can be identified through the shifting orientations between objects and bodies.3 If we compare the establishment of queer/LGBTQ archives in Taiwan and South Korea, we can see distinct histories and collection trajectories, as well as archival initiatives with similar goals. For example, the foundation of The Taiwanese Lesbian Cultural Memory Bank is a collection of lesbian magazines collected by program members, similar to Queerarch’s Buddy magazines and KSCRC campaign records. These magazines include Girlfriend (《女朋友》, 1994-2003) and Love, Happiness, Freedom (《愛福好自在報》, 1993-1995), which were founded and published by Between Us, the first lesbian organization in Taiwan. These publications catalyzed discussions and promoted new ideas. The archive contains mostly out-of-print or unreleased books, music, and documentaries, as well as records of bygone organizations and spaces. Among these materials, Between Us and Girlfriend serve as aggregates of important lesbian experience, creating a coherent throughline across more than 200 records of cultural memory and history.4 The Lesbian Cultural Memory Bank initiative also highlights a potential issue: lesbians (as well as bisexual and transgender women) are less visible in queer history than are gay men. How do lesbians themselves view their marginality in queer history, let alone mainstream history? In 1992, Rosawita, an Indonesian member of the Asian Lesbian Network (ALN), wrote that as women, Indonesian lesbians are more subject to social norms than are gay men, making it more difficult for them to lead free social lives or participate in social movements. In the same year, there was an incident where lesbians were secretly photographed and outed at a Taiwanese “T Bar.”5 This incident was included in the Lesbian Cultural Memory Bank as a representative event. Compared to long-established gay male spaces like saunas, gyms, and Taipei’s New Park, lesbian “T Bars” were essentially the only physical public spaces for generations of Taiwanese lesbians. They were also the target of constant voyeurism and treated as spectacles by mainstream society. At the same time, the development of the Internet in the 1990s also opened spaces for queer people to speak freely through more organized mediums. Combining the above discussions, both South Korea’s Queerarch and Taiwan’s Lesbian Cultural Memory Bank regard archival construction as an organic means of writing history. Both projects adopt a consciously contemporary interpretation of the archival process—”from archive-as-source to archive-as-subject”—remaining mindful of how power operates in knowledge production. These projects enact the idea of “archive as subject” by removing nationality, genre, and other rigid interpretive frameworks from objects, situating them within a “queer” historical formation. Personal scrapbooks, candid records, and Post-its clearly portray subjects actively documenting and archiving themselves. Moreover, the archives’ methodology and interpretation of objects do not merely focus on the objects’ contents, but rather on the historical moments and paths that emerge through the archives themselves, which interweave personal histories with mass media, queer movements, and even consumer culture. From this observation of the historical perspectives presented by Taiwanese and South Korean archives, a clear meaning of “queering” emerges. In recording erased and distorted narratives, these queer archives do not confine their subjects to mainstream or even male-dominated gay histories. Instead, they free these subjects from history altogether.

- 1 The Korea Queer Culture Festival (한국퀴어문화축제), also referred to as the KQCF, has been held every June since 2000. It includes parades, film festivals, exhibitions, and other related activities. It was later renamed the “Seoul Queer Culture Festival” because Daegu, Busan, and other places in South Korea held successive queer culture festivals.

- 2 See QueerArch Exhibition Notes, Note 2.

- 3 Ahmed, Sara. Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others. (Durham: Duke University Press, 2006).

- 4 “Between Us” was established on February 23, 1990. It was the first lesbian group in Taiwan, with over 4,000 members from all walks of life and age groups. The organization published the bimonthly magazine Girlfriend, which was founded on October 5, 1994 and ceased publication in April 2003 after a total output of 35 issues. Unlike other publications that focused on queer theory and literary discussion, “Girlfriend” emphasized the message “being a lesbian is a way of life,” recording a lesbian generation’s everyday life and culture.

- 5 On March 18, 1992, the “Taiwan TTV News World Report,” hosted by Catherine Chang, aired a segment called “The Rapid Rise of Lesbians.” The segment’s featured journalist used a pinhole camera to secretly film and expose Haven Bar’s patrons and staff. In another spliced Q&A clip, it was insinuated that a related performing artist was a lesbian.

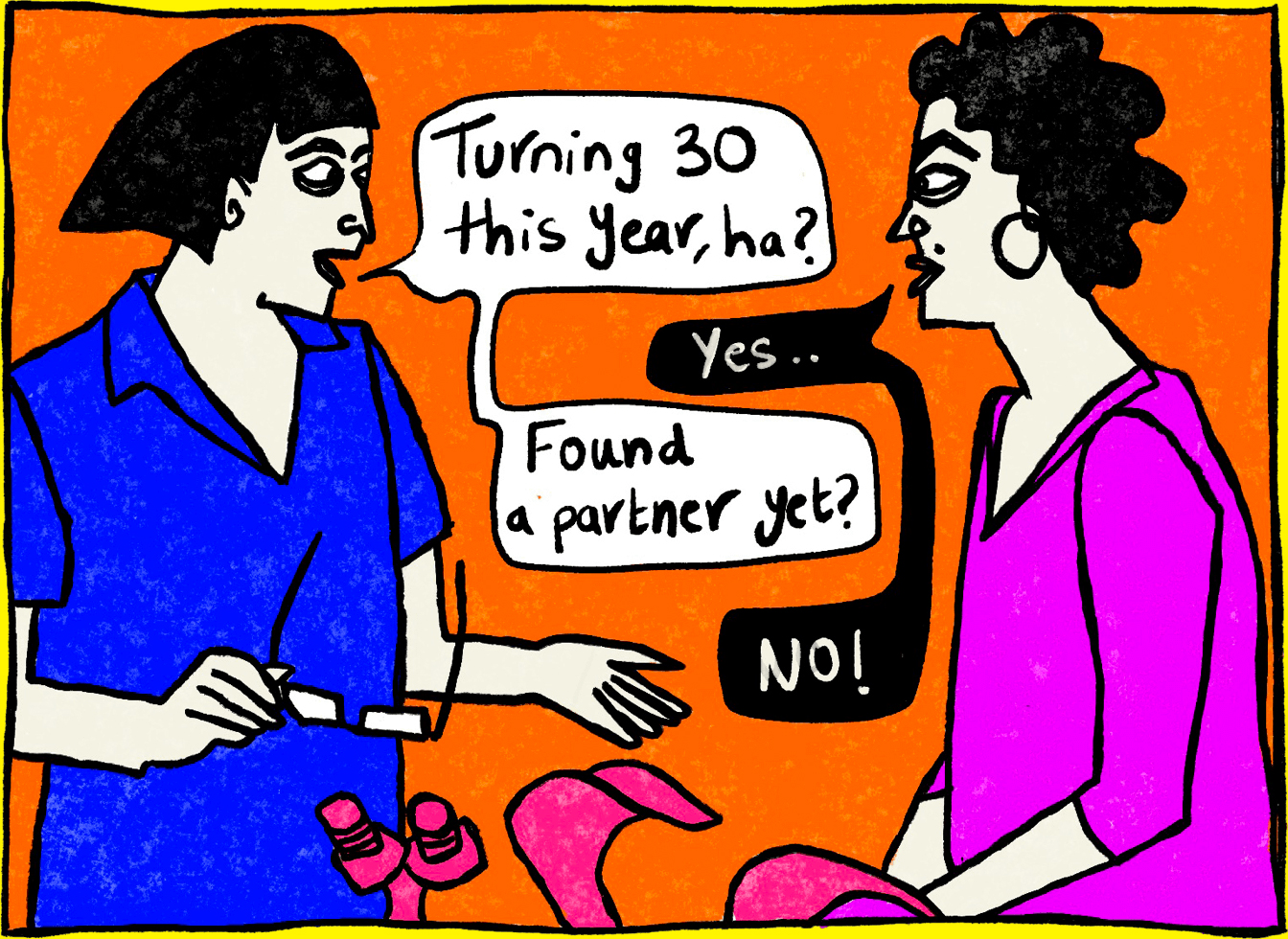

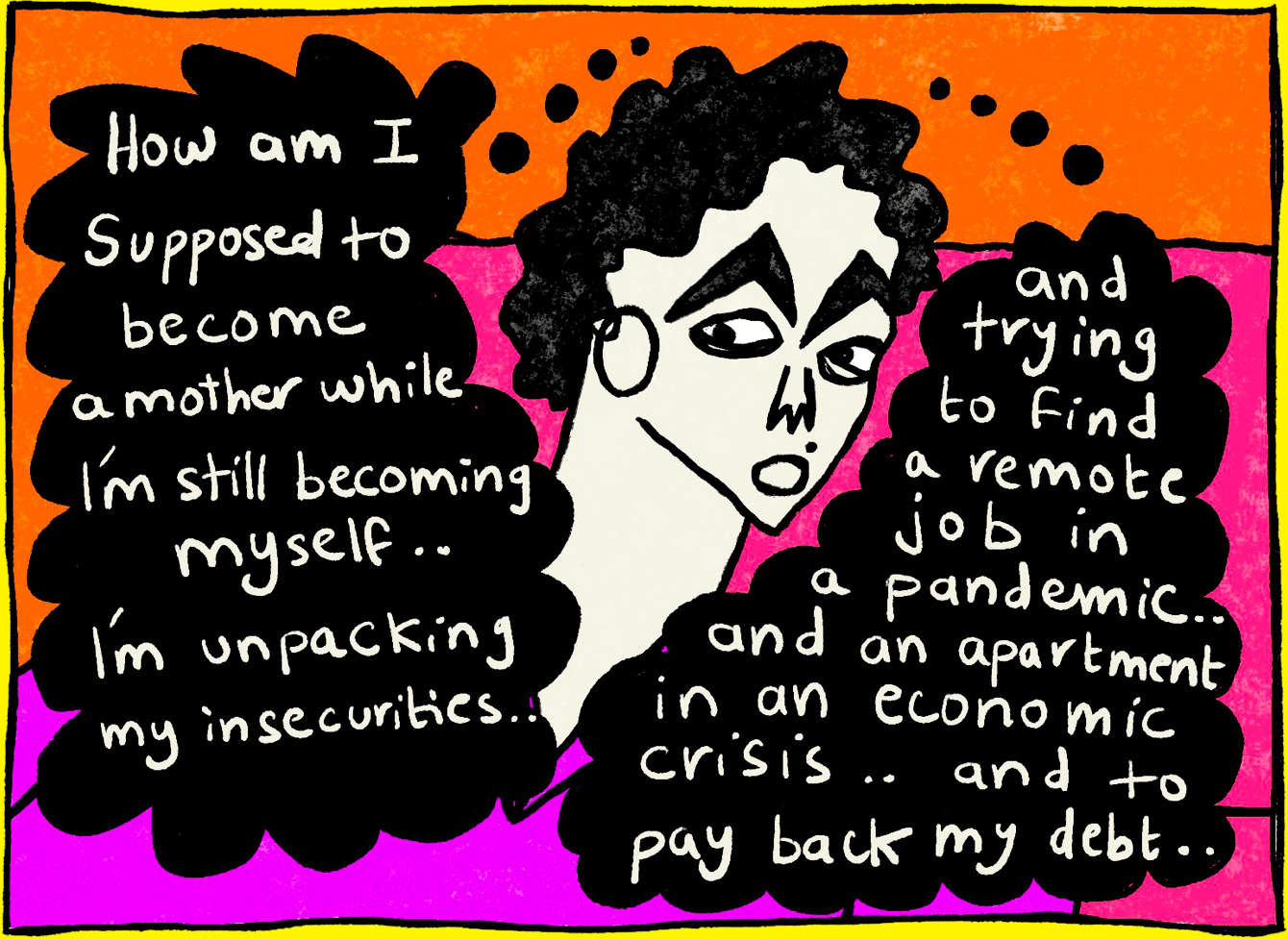

RAWAND ISSA

Rawand Issa is a Lebanese artist whose work often blends the political and personal. Her background is in writing as she was a journalist for five years after moving from the small town she was born in, El-Jiye, to Beirut. Her latest work is a graphic novel called “Inside the Giant Fish,” about a girl searching for her lost memories. For the comic below, Rawand explains “I was at my gynecologist doing a regular check-up but I left the office overwhelmed with feelings about my body, age, and self."

The largest protest in modern history took place in India last year when tens of millions of already struggling farmers took to the streets to protest the passing of three new laws intended to modernize the country’s deep-rooted agriculture industry. But by opening up agriculture to a free market system, the new laws took the first step away from protections like guaranteed minimum pricing for essential crops, and opened the door to private sales and investors. Doing away with the security that state-run agricultural marketplaces have provided since the 1960s would have set crop prices onto a volatile path. And for the nearly 800 million people dependent on farming for their livelihoods, that kind of instability and the threat of large corporations monopolizing the marketplace was simply unacceptable. In response, the largest agricultural workforce in the world mobilized during a year of sustained protests, and succeeded in repealing the farm acts in the biggest triumph for Indian democracy since independence from Britain. A fierce and commanding voice in the midst of these protests was that of Dr. Ritu Singh, a psychologist, social activist, and lifelong advocate for equality who stands out as an outspoken woman in a deeply patriarchal society. Her work on the ground organizing and leading demonstrations, and the roles of other women in the farmers’ protests, were invaluable to the movement’s success. CHIME spoke with Dr. Singh about her experience being on the frontlines of this historic movement, and the role that women played in its success. Below is her first-hand account.

Firstly, I believe that women shortened this protest. You know there is this identity of a woman being fragile, emotional, and kind of weak. And this government has tried to relegate that a woman cannot come out of the home, cannot protest, and cannot agitate. But this protest has given a different kind of an image to a woman. With our zeal and our enthusiasm, we succeeded, and we proved that we can do anything. Don’t challenge us. Before this, if government saw any women or any group of educated young people talking about things like equality or freedom or their rights or dignity, they might take it like, “Oh my God, they’re going to bring revolution? So we are going to stop them. Either we’re going to put them in jail or break their voice or just give them rape threats, death threats.” I have gotten multiple death threats. Multiple rape threats. So these kinds of things are butter on bread for us now—it is normal. Also, the men who were doubting us realized that we reached a level where we don’t fear jail, where we don’t fear to be put behind bars; we don’t fear that because we don’t have any other way. If we don’t come up and speak out, we will feel suffocated. Inside the four walls and outside also. So it’s better to go out, voice your views for yourself, and for others also who don’t have a voice. And advocate for your rights. So that’s what I’m doing. The father of the Indian constitution, B.R. Ambedkar, said “I measure the progress of a community by the degree of progress which women have achieved.” So this Kisan [farmers’ union], this farmers’ protest proved that—that women are no less than anyone, and here you see her roar. I will also say this, speaking on the basis of interaction with these women in the Andalon [the farmers’ rights movement], they were from day one doing journalism there; women were speaking on the stage or becoming advocates for the protest; and women were running community kitchens there. The aged women were cooking food for us that we were eating—women the age of 85, 95, 30, 40, 25. Even small children were there at the protest site. So there was no age limit for men or women. All those women from day one were steadfast that the new farm laws would be repealed. And we were not going to go back home unless or until this government will repeal these 3 anti-farm laws. So I have seen that, I have witnessed a kind of dynamic energy. I still have goosebumps if I talk about that protest, you know, going into the detailing of the protest. I tell you that I cannot put that feeling into words. It was kind of a feeling that, this is revolution, this is what we want. It’s like somebody has pressed you for a long time now, so you have got your voice, this is a freedom for you. So you are going to take this home. And especially if you talk about rural women, their basic livelihood and the future of our generation depends upon agriculture only. The agriculture income. So they were quite sure that they were not going to go home like this because we need to secure our land. I especially think that this protest has given a kind of employment for a few women who were working as scavengers or laborers. So they used to come to the protest site and clean the roads where we would eat food. So by the time it’s seven or eight in the evening, they used to get 100 or 200 rupees for the work that they have done. Two women also opened a school at the protest site, a kind of Paathshala in Hindi. From this protest we needed to show the government that we want education also, so we are going to educate students from this protest. We funded the school from our own pockets, nobody funded us. From our own pocket we bought books, pencils, copies and even school uniforms for those kids. And who were those kids? They were kids of laborers, they were kids of people who were working as scavengers near the protest sites. So they were poor kids with no food to eat, staying in slums... We were seeing that these kids were coming here in very dirty clothes. They don’t have shoes to wear. So let’s give education to these kids, so we tell them “Do you want to read?” We also gave employment to some teachers who came to teach at our school. A few girls who had just passed from their journalism course started their journalism careers at the protest. Many launched YouTube channels which were so successful they were monetized during the protest and now they’re earning also a good income. So this protest I’m explaining has different shapes and it has given meaning to people’s lives. It was kind of a revolution for all of us, it gave women a new identity and also an identity in front of men, especially men from small towns who think “OK women can only go out with me. She cannot go out alone, her father or her brother has to accompany a woman.” But this protest has shown the world and challenged the patriarchal thinking and the men of those communities that even you need us, we don’t need you. If you want to go out and you feel fear, take us along and you will become safe. (Laughs)

For this issue, CHIME has brought together trans activists Cecilia Gentili and Bianka Rodriguez for a discussion about their experiences as trans women in Central America and abroad. Meeting for the first time over Zoom, they share their insights into the discrimination trans women face in housing, sex work, the criminal justice system, and within the queer community.

CECILIA GENTILI: Let’s introduce ourselves to each other, let’s talk a little bit about who we are and what we do, and let’s keep in mind that the people reading this are young people who sometimes aren’t that involved in the subjects we’re talking about, so let’s be clear about what we’re talking about. Shall we start like this? Okay. My name is Cecilia Gentili. I’m very happy to meet you virtually, but very happy to get to know you and to have you right now as a connection and as a friend. I’m from Argentina, but I live in the United States, in New York. I came here in about 2000. I use she pronouns and I’m a transgender woman. I’m 50 years old. I know it doesn’t show at all, but I’m 50. I turned 50 on January 31st. I’m an Aquarius. And I live here in New York where I have a group of people that work with me who are all trans. We do consulting work for different companies and for the government to promote trans equity, while my activism is for my trans community, for my sex worker community, because I also worked as a sex worker for many years. I care a lot about people who are incarcerated or who have a history of incarceration, because I went through that too.

I also used a lot of drugs for a long time but now I’m clean.

I don’t know if I’m totally clean, I do let my hair down sometimes, but you see, well, that’s me! Tell me a little bit about yourself.

BIANKA RODRIGUEZ: Hello, Cecilia. Nice to meet you. I’m Bianka Rodriguez. I am a Salvadoran trans activist. Currently, I lead the organization COMCAVIS Trans, an organization that was born out of the efforts of several transgender women who met in the 2000s, but it wasn’t until 2008 that this empowered group of women said “We have to form a trans organization that looks after rights beyond HIV.” COMCAVIS is a legally recognized organization that works with women with HIV, because it embodies the essence of those fighters who were brave enough to fight the healthcare system in order to receive equal treatment—treatment free of discrimination, especially access to HIV treatment. And this also marks a history of various rights violations because one of our founders, Karla Avelar, who is now in exile, was also imprisoned. In 2017, Karla had to flee because of persecution and because she didn’t have the legal protection that the Salvadoran government should have given her. So the organization has three fundamental pillars, which are the incarcerated, people with HIV, but also those who have to flee because of persecution due to their sexual orientation or gender identity in our country and in the countries in our region of Central America. Over the years, I’ve been growing in my activism, but I believe that going beyond that activism means fighting for equal recognition, taking a stand to demonstrate the experiences that we are subject to as trans women. I certainly think it’s important to mention that, although there’s a depathologization of trans identities, in these more conservative countries, trans people are considered to have a pathology. They are considered mentally ill. Even public safety officials, in their role as protectors, as those who are supposed to provide security, murder us. And that’s a reality that I think is very hard for our situation and that’s why we’ve been stressing this, advocating, making it known that trans people have really existed throughout history. We’ve resisted during that history, in which our experiences have achieved many changes that have led to the empowerment that we now have. And that visibility has been because, unfortunately, many have had to die and many have had to go into exile and fight from other trenches in order to make this situation visible. Personally, I feel that I’m a woman like any other woman, although in El Salvador our gender identity is still not recognized. We have this legal vacuum. Recently, the Constitutional Chamber passed a favorable ruling so that our names can be legally recognized in government documentation, which is a big step, because it dignifies us as people. And I’ve focused a bit on advocacy, but above all on protection, because there’s no point in having a name, in having the right to exist, if violence is prevalent in our country. And we’ve opened up a house of protection, a shelter for LGBT people and above all for trans people, because I really believe that, although it’s the work of the state, they’re not working, they’re not responding to this need. And it’s up to us as empowered women to go out and search, to see where we can find something that the state doesn’t provide, which is protection and, above all, respect, and that in the end, among ourselves, we take care of ourselves.

CECILIA GENTILI:Yes, this is true. Well, first of all, you’re a total idol. I’m totally in love with the work you’re doing. I was exiled from Argentina, and I have a lot of respect for people who stay in their homeland and take a stand. At the time, in 2000, I said “I can’t stay here because I’m going to die.” I saw myself, I saw death so close so many times that I said “No, I can’t, I can’t stay here.” And that’s why I went into exile, but I have a lot more respect for my brothers and sisters who do the work in their country. So I want to tell you that I’m very proud to know about all this work. And I have no doubt that they’re going to achieve everything, they’re going to achieve all the things they set out to do. Little by little, but they will achieve it. As you said, we’ve been in this world forever. Indigenous communities all over the Americas, right? My grandmother was Indigenous and her best friend was trans, and nobody knew. When she died, they discovered that her genitals were different from what they thought, but nobody knew. And that confirms the fact that the idea of gender that we’re dealing with today is a European construct that was exposed to us without asking us, and that’s why people like you and all my friends there in El Salvador are doing this work. I love it. Congratulations.

BIANKA RODRIGUEZ: Thank you. I also admire the work that you’re now doing in another part of the world, especially for transgender people in prison. Because I think you’re dealing with many violations in prisons... sexual violence. And I tell you this because when we visit the prisons in El Salvador, we hear about these experiences of being sexually abused by other prisoners, but also by prison officials who, in theory, are there to guarantee our safety, so that we don’t escape from prison. And really, when you say to me “I’m a 50-year-old woman,” I say that age doesn’t matter. What matters is the struggle that we carry on, and that we have to recognize that the generations are changing, but above all that those who came before have been paving the way towards equality. And now it’s up to the new generations to take up what other women warriors, fighters like you, have built. I’m only 28 years old. I started activism when I was 22 and I didn’t understand how my feminine expression was harming society, but nevertheless I was like, well, I need to do something, I need to know who I really am and why society rejects me as such. Later, I saw this similarity in many more trans women. I said “Well, we have to do our part in society and change these mentalities, and that’s how we have to work with our communities, in our social circles, to transform this, what a trans person is, because many understand the meaning very differently. It’s not that we go through life saying “Look, I’m trans,” but rather that I’m a woman just like any other woman, and having a different biological sex doesn’t make any difference to me. In other words, even in the diversity of women, there’s a wide spectrum of what it means to be a woman, but as you mentioned, these European gender roles have distorted who we really are, and we’re fighting to have our own identity.

CECILIA GENTILI: It brings me so much joy to know that you have this story at such a young age. And it’s the truth, grandma wants to go to bed early, grandma can’t go to all the marches anymore, grandma wants to rest. So, girls, knuckle down and start working. It’s important that we create spaces for this new generation. And one thing that struck me is when you said that sometimes the people who attack us are the ones who are supposed to protect us. And when I talk about the sexual violence I experienced through the justice system, when I talk about it, the first thing people think is that I was attacked by other prisoners, which was also the case, but my worst experiences were with guards, who were the ones who attacked me sexually, physically, psychologically. But how can anyone think that a woman like me should share a prison with a hundred men, you know what I mean? Who would think that could be a good thing? It’s incredible how much trouble and insecurity is created by not recognizing one’s gender. It would be so simple to recognize our gender and let us live our lives as any other women, even as prisoners. I don’t understand how governments do nothing. And, I’ll tell you, now in Argentina, like here in the United States, you can change your name, you can change your gender marker, you can change your birth certificate. But sometimes I think that those things make people think “Oh! It’s all good.” At the same time that these things are happening in Argentina, the number of women murdered every year keeps going up and up and up. And I always ask myself “How can these two things coexist at the same time,” don’t you? One step forward and one step backward. As much as there’s progress, I think it’s embedded in the public perception that people like us, in this case trans women, and also many people who are queer or gay, don’t have the right to life, you know what I mean? Like we don’t have the right to be happy and live our lives like everyone else. And that justifies so much violence. I’ve suffered a lot of violence in Argentina, and also when I lived in Brazil. It’s so heavy and sometimes you say, “Oh, you know, I got to live to 50 years old and most of my peers my age aren’t alive; they’ve all died of HIV, of violence, from having medical conditions from which they couldn’t heal.” But life has been so difficult only because I don’t think there’s an understanding that people like us have the right to live like everyone else.

BIANKA RODRIGUEZ: Yes, that’s right, and it is even more worrying that, at a global level, for example, there are still almost 40 or 50 countries where it’s still a crime to have a sexual identity or orientation that’s different from the norm, from heterosexuality. And I believe that this leaves us with the message of: we come from backgrounds where it was once a crime to be free, to have an identity or an expression in line with what I feel comfortable with. As you mentioned, about hate crimes and particularly about trans women, the system is plagued by impunity, because even when we’re murdered, we don’t have the right to reparations and justice like anyone else. And, without a doubt, many young people die simply because they’re trans. And at this point, I think it’s important not to continue to silence these injustices, because people think that it’s abnormal, even within our own populations, within our fellow trans women, they think that being trans is a bad thing. And it’s not a bad thing. Rather, it’s something natural that we can’t change even with the worst conversion therapies. This is the message that needs to be conveyed to society, which is to say: in how many countries in the world is it a crime to be heterosexual? None. But why do you have to criminalize our sexual orientation or our...

CECILIA GENTILI: ...our identity! Sometimes, when people say to me “Oh, you chose to live like that.” I say “Do you think I would have chosen to live the life I’ve had to live with so much pain, with so much violence, with so much insecurity? Do you think that, if I could choose, I would choose the shitty life I had to live?” No one chooses this! If I could choose, I would have chosen a quiet life, like everyone else. This is not a choice. This is my life, this is who I am.

BIANKA RODRIGUEZ: Right. And even though people in society think “It’s your choice,” a choice means I would have had several alternatives to be whoever I wanted to be, but no... We don’t go through life with this option of saying “Well, today I’m going to be trans, tomorrow I’m not. The day after, I’m going to be gay. The day after, I’m going to be...” That’s not how it is. And people think that with these messages, they make us feel like we’re... free! And it’s not freedom. I think being chained to a cycle of violence, a cycle of discrimination is like a determining factor, because even though we recognize our own identity, you always have to, at some point in your life, explain why you’re trans. Because it’s not something that disappears overnight. It goes on and you have to keep reaffirming to other people that you are a woman, but that you made a transition. And I don’t think that should happen because there’s still a lot of ignorance, even in countries where they have the most advanced laws. I think that this is a way to tell our life stories, to say that this has happened to me and it’s not a choice, but a story of struggle, of resistance. Because I think that those who judge us don’t have enough courage to put themselves in our shoes, in our bodies, to be able to live even one day of what we experience. Because not only are we killed for being trans, but we’re also killed for being women, because of this society. That’s the message, that women are—I mean, the term woman, the term feminine is even lower than being a man.

CECILIA GENTILI: It’s toxic. It’s toxic. Another thing I see that has a lot to do with it is colorism because, for example, in countries like Argentina, people with whiter skin have much more privilege. And sometimes trans girls who are dark-skinned suffer much more, like here in the United States... Black women, Black trans women. Sometimes, it all comes to a point when being trans, being a woman, and not being white puts you in a very, very, very complicated and very dangerous corner. And people can’t understand that. Bianka, we were talking about the problems that our community faces in our home countries, which sometimes I think are not so different from what happens here in the United States. I think that here in the United States, there is more of a right to complain and maybe to have someone listen to you. But what are the problems that you see most in El Salvador right now for trans women? How is housing, employment, education, health? Tell me a little bit.

BIANKA RODRIGUEZ: Well, when we talk about the context of our countries, we have to start from the phenomenon of violence. Even we, as defenders, as organizations, we’re astonished. We come in and we’re astonished, for example, with reports, with the Inter-American Commission itself in El Salvador, the Human Rights Ombudsman’s Office has established a life expectancy for trans women in El Salvador...

CECILIA GENTILI: 35, right?

BIANKA RODRIGUEZ: 33. The Commission says it’s 35 for the region. In El Salvador, a trans person lives two years less. In other words, a trans woman or trans man can live a maximum of 33 years in El Salvador before being killed or murdered for reasons of gender identity or gender expression. And the fact is that this violence often forces us to move, oftentimes forcibly, from communities, from regions, from towns, in order to seek protection and feel safe. And when we don’t manage to achieve this, we have to go to another country, to seek international protection because we’ve run out of strength to continue fighting in this country that only offers us discrimination and violence. And I don’t think this is very different from South American countries or other Central American countries, where, as you mentioned, being a trans woman is an experience, but beyond that experience, it puts you at a disadvantage. In other words, being a trans woman in El Salvador means being the victim of nine times more violence than a cisgender woman. And this isn’t coming from me; it’s coming from the Human Rights Ombudsman’s Office and government institutions that have carried out these studies. And it’s sad to know that our reality does not change and that year after year, day after day, we fight against this violence, demanding and demanding, before our congresses, before our courts, that these rights be respected. However, there’s no will to change and transform this sexist, xenophobic, misogynist, transphobic reality against trans women or people of a different sex or orientation. However, for example, when we talk about this violence, we must also be aware that in the social sphere, there are many other forms of violence, such as those mentioned in the workplace, in education, in health. Because you’re trans, you’re pigeonholed even when you go to the doctor, because they think the only problem you can possibly have is HIV. In other words, you can’t go to a health facility and say “Look, I have a headache.”

CECILIA GENTILI: I burned my arm!

BIANKA RODRIGUEZ: Right! And they ask you “Do you have HIV?” Well, everything is conditioned by the fact that there’s a stigmatization. And I’m of the mentality that, hey, I’m coming here because I have a headache, I have the right to have a headache, but just because I have a headache doesn’t mean that I have HIV.

CECILIA GENTILI: But that’s violence too, Bianka. That’s state violence, that’s violence created by the state that doesn’t stab you, but kills you a little bit at a time, right?

BIANKA RODRIGUEZ: Right.

CECILIA GENTILI: But in the end it kills you anyway, because if you can’t go to the doctor, if you don’t pay attention to your health, if you don’t have the possibility to study, if you don’t have the possibility to get a job like anyone else... Your life is endangered in different ways. I saw it, I saw it a lot. For a long time, I said “Ah, me, I do sex work because it’s something I chose.” But today I say “Yes, I chose it, but there weren’t many options to choose from.” It wasn’t that I had the choice of “I’m going to be a lawyer, I’m going to be a hairdresser, I’m going to be a teacher, I’m going to be a domestic worker or I’m going to be a sex worker.” There was no choice! The only option was to be a sex worker. So how much of an option is it when it’s the only option, right? And I think that’s why it’s so important that, in my struggle, I believe that sex work should not be criminalized because, for many of us in different parts of the world, it’s still the only option we have. The only way we can put food on the table for ourselves, for our families. And the fact that it’s criminalized creates this vicious circle where you don’t have a job, you start doing sex work, you get arrested, you go to jail, you suffer violence in jail, you get out, you don’t have a job, you do sex work... and you can never break it. We can never break it. But all of that is the responsibility of the government because of the laws they’ve instated, like the gender laws, like the laws that don’t include us, like the laws that criminalize us for things like sex work. That’s why I think it’s so important that we do the work. What’s the situation like in El Salvador now, for people doing sex work?

BIANKA RODRIGUEZ: It’s similar. Being trans, for example, makes it impossible for you to access formal education. When you can’t access formal education, you have to access these circles of violence, because many people think that, as you were saying, sex work is a choice for us, and it’s not a choice. Because if they gave me the opportunity to study, to train professionally with my own gender identity and expression, to change my reality, I would have other options. And as you mentioned, this is a vicious circle, a circle of violence that we can’t break because there are no opportunities for us as trans women, because we didn’t have an education. And how are we going to compete for a formal job if we don’t have those skills? Because they’ve denied us a fundamental right, which is education. And, above all, when we get into sex work, we do it, as you mentioned, to survive and because that’s the only option that our governments relegate to us, because there’s been no adaptation of laws that guarantee our inclusion in these rights to work, to education and housing. Because even when you want to rent, there are people who won’t rent to you because they say it’s prostitution money, there’s a huge stigma that it’s ill-gotten money.

CECILIA GENTILI: You just reminded me that a couple of years ago—and some might say “Oh, that’s in El Salvador, that doesn’t happen in the United States”—but a couple of years ago, I wanted to rent a house. I called the real estate agency, I sent all my papers, I was already working at a non-profit organization, I had a clinic for trans people, I was making money, I was paying my taxes. They told me “Ah, if you want the house, send in your documents and we’ll see.” They saw my documents; everything was changed, my gender and my name. They looked at the documents, they called me back and they told me “Yes, the house is yours.” When I went to see the house the man could tell that I was trans and told me he wouldn’t rent to me. So that does happen right here in the United States. So, what I wanted to say is that these things happen all the time. And beyond the fact that, many of us don’t have the money to rent something, and when we do, people believe it’s ill-gotten or that we won’t be able to pay. So, there’s always a way we’re being neglected, continuously neglected. But Bianka, tell me a bit more about you. This is your life, being an activist. This is what you’re going to do.

BIANKA RODRIGUEZ: Well, for the moment, yes. I mean, I think my dream was to finish my degree because I got to the third year of university studying Agro-industrial Engineering.

CECILIA GENTILI: Oh, how nice! Do you like the countryside?

BIANKA RODRIGUEZ: Well, not so much the countryside, but the career has to do with agriculture, food, and veterinary science. So like the manufacturing of food products from agriculture and all these issues of produced food, as well as medicines for animals and all of that. So, my dream was to get that degree, but unfortunately I ran into the barrier of transphobia within the university. And I think many of us have to decide, like me, whether to continue with your identity or continue with your studies. And I preferred to continue with my identity, with being who I am, because for many years I lived shut away, mistreated, violated by my family... And I said “No, if I was able to overcome what my family did to me, why can’t I overcome this? Why can’t I say ‘no, you’re not going to interfere with who I am and my freedom’?” And to this day I’m still in activism and I think I’m going to stay here for a while. But then I know that I have to continue to develop and do what I really want. I love nature, I love animals, I love many things, but I know that my life has to change, because if we’re achieving these things, it’s in order to achieve those dreams that we’ve always had, for example, to be an engineer, to be a lawyer, to be a professional who contributes to society every day, and not necessarily with our activism but, as I mentioned, from our trenches. A lot can be achieved by transforming our social environments, especially the environments of our friends, because I really believe that, in the end, not only trans women were born for activism. And I think that this is a powerful message that we can send: that trans people are now taking a stand and resisting, but it’s because we want an egalitarian, fair future, where inequalities disappear. Because many of us—even if they say we live off sex work—live in poverty, poverty that nobody understands and, as you mentioned, we also have to support our families. We support our nephews and nieces, our little brothers and sisters, our parents. And...

CECILIA GENTILI: And ourselves! All of this doesn’t come cheap. It’s all very expensive!

BIANKA RODRIGUEZ: Right. And for people, even for our families, we exist because of that, because we’re a source of economic income...

CECILIA GENTILI: Sadly.

BIANKA RODRIGUEZ: ...and sadly, sometimes they recognize your identity and sometimes they don’t, but you’re obligated to contribute, or contribute financially, to the family. It’s sad, but it is also the reality for many trans women.

CECILIA GENTILI: That’s so true. I’ve been through it, many of my friends, we’ve been through it, we’ve ended up buying the love of our families with money. And that’s the reality for many of us. And I love what you were saying, and it struck me that it would be nice if we didn’t need to be activists, wouldn’t it? Because we could be, if we had the opportunity, anything we wanted to be. You would be an agricultural engineer. I played the French horn, I went to music school. I would have been a soloist and all the girls and boys could do whatever they wanted, and there would be no need to be an activist. I wrote an article a few years ago where I asked if the T is still part of LGBT, because actually, a lot of the times that I’ve experienced transphobia—you think that transphobia mostly comes from cisgender people and straight people—but unfortunately I have to say that a lot of times the transphobia has come from our gay brothers, gay men, and from our lesbian sisters, who have so often—mostly lesbians—left us out, who haven’t considered us women, right? And I say that I’m very passionate about the idea of family, like many of us who have had many painful experiences with their family. I personally like to think of the LGBT community as one big family, but I can’t help but mention the fact that a lot of times it’s been mostly gay and lesbian people; not so much bisexual people because they’ve always been good to me. But a lot of the times I’ve experienced transphobia and being sidelined, it’s been by my own LGBT community, and part of me wants to say “Oh, I’m going to create a world where it’s just trans people. That’s what makes me happy, just to see myself among trans people,” but the reality is that we live in the world and the world isn’t trans and we need to be part of any space, but mostly the LGBT space, because we are the T, but many times—I don’t know about where you live—but here many times transphobia comes from our gay and lesbian peers, and that’s something that we have to fight all together, because I always tell them “After they kill me, they’re going to kill you.” I don’t know what the situation is like in El Salvador with your gay and lesbian peers. Is there solidarity among the community?

BIANKA RODRIGUEZ: In El Salvador, there’s actually more problems with lesbian women’s movements because there is a part of the feminist movement that doesn’t recognize trans identities, especially trans women who may be trans feminists. The attacks, as you mentioned, are really from within the community itself, from men and also from lesbian women. But also, we have to recognize that it’s because of the privileges they have, because a gay man doesn’t suffer the violence that we suffer as trans women, because many gay men have to keep their sexual orientation quiet, which is fine because it’s their freedom in order to obtain all these privileges that we don’t have. And it’s also sad to mention that there are gays and lesbians who get into politics, who are civil servants, members of parliament, but when they get into politics they don’t really continue to promote our rights; they put even more obstacles in the way and legitimize the violence that we trans people suffer or face. Because I remember, for example, in 2016, there was an openly gay man in the Legislative Assembly of El Salvador and we insisted to him a lot, “promote the gender identity law because it’s crucial.” He had the right to initiate a law as a deputy of the Republic, but he said “No, I won’t dare to do this.” And then they really complain because trans women are more visible. For example, with regard to the pride march, the celebration of gay pride, why do they call it gay pride? Because it’s not gay, it was LGBT pride. Because the one who started the fight was a trans woman; the one who threw the first stone was a Black trans woman. Because there’s even racial discrimination, as you mentioned, of trans women. For example, we have to be slim, put together...

CECILIA GENTILI: Beautiful, blonde...

BIANKA RODRIGUEZ: Right.

CECILIA GENTILI: Made-up, with a cinched waist, heels, nails...

BIANKA RODRIGUEZ: Right, and it’s not our reality. There are trans women here who are of African descent, who are Indigenous, who don’t have those kinds of features...

CECILIA GENTILI: European beauty.

BIANKA RODRIGUEZ: Right, European beauty.

CECILIA GENTILI: And then of course they call you “the Indian.” “There goes the Indian.” You know what I mean? As if it were a bad thing. Yes, Indian! So what?

BIANKA RODRIGUEZ: And I really believe that this is what we’ve had to deal with in history: even within our own collectives there’s a divide. But beyond divisiveness, there’s transphobia toward identities, toward our experiences and, above all, toward our rights. Just because you’re gay, lesbian or bisexual doesn’t mean that you can respond to the demands of the collective. And that’s why many of us have had to empower ourselves, go out in the streets, and some of us have even had to participate in public policy itself in order to be able to introduce these legal initiatives. For example, there’s Tamara Adrián in Venezuela, who was a trans woman who fought in her congress in order to promote these laws.

CECILIA GENTILI: Well, I think Bianka for senator. I see it in your future. Bianka, senator. Bianka, president. Bianka, I’m coming and I’m voting for you.

BIANKA RODRIGUEZ: We have to dream that at some point in our history, a trans woman can also be president of a country.

CECILIA GENTILI: And don’t doubt it, that person could be you.

BIANKA RODRIGUEZ: Of course.

CECILIA GENTILI: I see it, I see it in your future. I see a lot of very good things. It was great to meet you. I love to know that there’s activism, and that there’s activism specifically in El Salvador, and that you are doing this work. And I want to say a huge thank you for doing it and for all that it means. I want you to know that you’ve got a friend in me. I would love to meet you in person some time soon.

BIANKA RODRIGUEZ: Hopefully soon.

CECILIA GENTILI: Let’s keep in touch. Come and visit me and I can come and visit you when I get my citizenship, I will visit you.

BIANKA RODRIGUEZ: Great. Perfect. Thanks so much to you as well, Cecilia. It was lovely to meet you, to be able to chat a little bit despite talking about things that... destroy us as women, but really build us up and strengthen us in order to continue standing firm in that we’re not going to back down for our experiences and for our rights. And I really hope I do get to meet you in person.

CECILIA GENTILI: I would love that. I love what you said, we don’t give up. We’re not going to give up. It was a great pleasure. Take care.

Faaolo Utumapu-Utailesolo is the Program Officer for the Pacific Island Countries with the Disability Rights Fund and Disability Rights Advocacy Fund, supporting organizations of persons with disabilities in the Pacific. She recently consulted for Women Enabled International (WEI) on their gender-based violence report that was carried out in Samoa.

Globally, women with disabilities make up approximately one-fifth of the world’s population of women but are two or three times more likely to experience certain types of gender-based violence (GBV). In Samoa, GBV rates are high, and people with disabilities are especially at risk. In one study conducted by the Samoan Ministry of Women, over 85% of female respondents with disabilities reported experiencing physical violence. This subject is personal, because I, myself, am also a person with a disability. People see us as different, and I think that may be a reason women with disabilities experience a disproportionate rate of GBV. For instance, in my experience in the field, those who are deaf or those with intellectual disabilities tend to be the ones who experience more violence or discrimination because they aren’t perceived by some people as having a valid voice.

Abusers think that the people who are deaf will not tell anyone or that a woman with a disability doesn’t have the mental capacity to tell right from wrong and act on it. They think that victims of GBV won’t report whatever it is that’s happening to them. It’s an old attitude that isn’t unique to Samoa but is still very prevalent. The laws and the regulations aren’t strong enough to mobilize people with disabilities to report cases of violence and to ensure that when the reporting does happen, that it’s actually being taken seriously. This goes for all people with disabilities, including young men and boys. They too have suffered. Since 2016, steady progress in advancing disability rights has been made in Samoa through policies and investment in the Samoan disability community. We have some cases of people with disabilities who have been abused that have actually made it to court and there have been people who have been in prison because of what they have done.1 We are making progress, but there is more work that needs to be done so that the community can more easily report this kind of violence and abuse. It’s all very well for us to read the research and the reports that people with disabilities are more likely to experience violence and abuse, but it’s nothing like hearing from women themselves about the experiences that they’ve had. Working with Women Enabled International, an international human rights organization working at the intersection of gender and disability, and the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), I interviewed a range of people with varying disabilities and asked them to share their experiences. Their stories were compiled into a groundbreaking, soon-to-be-released needs assessment report. I have been very touched and humbled by the experiences that people shared with me and how brave they were to come out and share their stories. I’m talking about only a handful of people with disabilities sharing their stories. Imagine, there are so many people with disabilities out there who are facing violence and are unable to use their voice, to shout out and demand justice. Hearing how they experienced this violence at such a tender age—it was shaking. Especially from those who are now becoming young adults and have been affected by one form of violence or the other at a very young age. Some of these young people were just children when they were experiencing this abuse. When you hear those stories as a journalist, but especially as a parent, it takes a toll on you. I’m really hopeful that the reports made with WEI and UNFPA will make clear what is needed to improve the services available to women with disabilities and make them more accessible. I also hope to raise awareness amongst the parents of children with disabilities to be vigilant about protecting their young people so that they don’t encounter this kind of abuse. I believe that all persons deserve to have their inherent dignity respected and - despite what abusers may believe - we do have a voice.

To receive a copy of the full report, Women and Young People with Disabilities in Samoa: A Needs Assessment of Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights, Gender-Based Violence, and Access to Essential Services, visit www.womenenabled.org

Women Enabled International is an international human rights organization working at the intersection of gender and disability around the globe to: respond to the lived experiences of women, girls, and gender minorities with disabilities; promote inclusion and participation; and achieve transformative equality. (@WomenEnabled)

To support women with disabilities in Samoa, Organizations for Persons with Disabilities (OPDs) like Nuanua O Le Alofa (NOLA) do a lot of work to empower and train their members and to raise awareness within the Family Health Association, the sexual and reproductive health services provider in Samoa.

- 1 Samoan Special Needs Instructor Admits Sex Crimes, Radio New Zealand, Web, 20 Feb 2015. https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/pacif-ic/266642/samoan-special-needs-instructor-admits-sex-crimes

EDITOR IN CHIEF

- Adam Eli @adameli

ART DIRECTOR

- MP5 @mp5art

CONTRIBUTORS

- ELISA MANICI @elisa.manici / PH: HELENA FALABINO @helenafalabino

- ASSA TRAORÉ @assa.traore_ / PH: MÉLANIE REY @curiouser.and

- ENO PEI-JEAN CHEN / TRANSLATION BY ARIEL CHU @spindly.waif

- KIRA WEI-HSIN JACOBSON @kira.object

- RAWAND ISSA @rawand.issa_

- DR. RITU SINGH @officialdrritusingh / PH: SIMRAN CHHABRA @PintSizedPataka

- ISABEL MAVRIDES-CALDERÓN @powerfullyisa

- CECILIA GENTILI @ceciliagentili72 / PH: SCOTT HEINS @scottheins

- BIANKA RODRIGUEZ @comcavis_trans

- FAAOLO UTUMAPU-UTAILESOLO

- CHIME @gucciequilibrium

- CHIME ZINE EDITORIAL ASSISTANT Stephanie Barclay

- CHIME ZINE PHOTO EDITOR Jacopo Gonzales @jacopogonzales

- COVER IMAGE COURTESY OF ISTOCK.COM/MEINZAHN

- TO GATHER TOGETHER TITLE COURTESY OF DANIELE LOMBARDI