At CHIME FOR CHANGE, we want to see a future with complete gender equality. In a world filled with systemic discrimination, that goal feels daunting, but we simply don’t have time for fear or hesitation. Every day people are suffering and dying from gender-based violence and discrimination. We can’t tell you how to completely eradicate this, but we can absolutely give you some places to start. This zine features 16 contributors from different parts of the world who are fighting for gender equality. We asked our contributors to explain what they do, and most importantly how you can join them. Because they can’t do it alone. Change may start with a Chime but can only truly be achieved when we put aside our hesitation To Gather Together.

ADAM ELI

For the past 20 years of my life, I’ve been a woman with a physical disability. I used to internalize the ableist narrative that we, the people with the disabilities, were these sort of broken, unworthy, incomplete beings who had to feel ashamed for who we are or how we look, with no place in or ownership of this world. But, why? If we go back to the most shameful moments in our collective human history, we can find records that we, the disabled ones, have been hidden, experimented on, mocked, and killed based on the belief that we don’t qualify as what the powered owners of these narratives have deemed worthy. In every instance in history when our voices have been taken away from us, the owners of that narrative have continued forging a path further and further away from where we stand (or sit) because it might seem convenient to ignore or forget about our existence. That said, it makes you wonder how one can truly belong and BE in the world, especially if you have a disability and you are a woman, when that world inun- dates you with a double dose of discrimination. Our fight for our rights as women has been a long painful one, but to this day we still find ourselves lacking in representation and in a wider understanding of the importance of intersectionality in our gender equality fight. I could share several examples of being called to action by my activist peers to appear in marches, discussions and strategic gatherings, only to find that our needs were never accounted for. Once, a local feminist orga- nization invited us to a networking event to discuss future actions and urgent matters. Eager to join arms with our sisters, we arrived only to find the location wheelchair inaccessible and without a sign language interpreter for my fellow deaf activists. We felt completely excluded and terribly disappointed. Even within our shared activist circles our perspectives and needs are still ignored. To quote disability rights activist Stephanie Ortoleva, we have become THE FORGOTTEN SISTERS.

It is both a systemic invisibility and inclusion issue. People with disabilities represent 15% of the world’s population.1 Of that, nearly 1 in 5 women live with disabilities.2 So, clearly, we do exist, but when we are not included as full participants in data-gathering, analysis, and solutions, we, again, BECOME INVISIBLE. Let me share some risks of invisibility. In Mexico, where I live, there were approximately 3,430 femicides in 2017.3 Of women who have suffered violence by a boyfriend or husband, 64% of incidents have been catalogued as cases of extreme violence.4 Of all that data, we do not know how many of them are women or girls with disabilities. We do not count, even when we are dead. Women like me are at risk of sexual violence at a rate that is around four times greater than able-bodied women.5 All of this is a result of insufficient legislation and a lack of effective public policy and representatives. Therein lies the importance of shining a light on us. Not to divide us from all women, because we do share the same fight, but to understand the implications that disability has on gender and vice versa, so that we will no longer be hidden or ignored—so that we will no longer be the forgotten sisters.

Collaborate with the cause: Join the Mexican Women with Disabilities movement (@mexicanascondiscapacidad) or participate with international organizations such as Women Enabled International (@womenenabled) or UN Women to help women and girls with disabilities be visible so they can take part in decisions for their rights.

1 “World Report on Disability,” World Health Organization, 2011. 2 “The Empowerment of Women and Girls With Disabilities: Towards full and effective participation and gender equality,” UN Women, 2018. 3 Robbie Whelan, “‘A Horrible Culture of Machismo’: Women Struggle With Violence in Mexico,” The Wall Street Journal. 4 “Estadísticas a propósito del Día Internacional de la Eliminación de la Violencia Contra la Mujer,” The INEGI (National Institute of Statistic and Geography in Mexico), 2018. 5 “On the situation of women from minority groups in the European Union,” European Parliament report, 2004.

I am a proud, queer, mixed-Black woman. It’s such a simple sentence, yet one I struggled to say out loud until I reached adulthood. I always knew I was Black, but by default, lived life as though I was straight and cis-gendered. I didn’t even know it was possible to be queer and Black, I didn’t even know what it meant to be queer. But I am, I do. I am a proud, queer, Black woman and I no longer struggle to say it. Reading work from the likes of Audre Lorde and Angela Davis gave me the language to understand and articulate my identity, but it is women like Lady Phyll who have allowed me to see it in practice, tangibly, right here in London. Phyll Opoku-Gyimah is the executive director of Kaleidoscope Trust, the UK’s leading LGBTI human rights charity, which campaigns for queer rights across 44 countries in the UK Commonwealth. The queer community lovingly refers to her as Lady Phyll because in 2016, in protest of imperialist anti-gay legislation in the global South, she refused the title of MBE (Member of the Order of the British Empire), an award given by the Queen. In turning down the award, Lady Phyll said that as a Black African lesbian, she couldn’t accept an MBE when LGBTQ+ people “are still being persecuted, tortured and even killed” by laws put in place by the British Empire. I first met Phyll a couple years ago when she invited me to join UK Black Pride—Europe’s largest celebration for LGBTQ people of African, Asian, Caribbean, Latin American, and Middle Eastern descent—of which she is the director and co-founder. UK Black Pride is a space like no other—it centers the voices, talent, troubles and joys of queer people of color in a way that few other spaces do. For the past few years, in almost every major city, Pride celebrations have fractured as activists and community leaders, rightfully, claim that Pride has lost its sense of political purpose.

During this pivotal moment, community-building work by activists like Lady Phyll is absolutely invaluable. As a volunteer at UK Black Pride I got to witness and understand the intensive emotional labor that goes into creating and holding space for so many queer people of color. I spent a lot of time with Phyll, having very honest and frank conversations about how to take care of ourselves whilst doing all this, because as pressing and vital as the work may be, we must recognize the impact that it can have on our emotional selves. Every time I see Phyll, she embraces me with so much love and asks me, “But how are you really doing?,” and each time it makes me stop and pause. People like Lady Phyll remind me that it’s possible to be a loud, proud, queer Black woman who cares about her community as much as she does about herself. She reminds me that I do not have to negate my own self, or my own well-being, to sustain and build community. Only through the commitment to loving ourselves, not just through words but through practice, are we capable of loving, caring, and supporting our community. Lady Phyll is a reminder that the work we do is beyond any single person. We are doing the work of our queer Black ancestors, we are continuing their legacy, and in doing so, planting the seeds for the next generation of QTIBPOC to build upon and grow from. It doesn’t start and stop with one person, and this work most definitely doesn’t start and stop with me or the great Lady Phyll.

Get involved: Support the Black and queer community by volunteering with UK Black Pride (@ukblackpride) or by learning more about Lady Phyll (@ladyphyll) and the Kaleidoscope Trust (@kaleidoscope_t).

RaFia Santana is a Brooklyn-based Black, queer multidisciplinary artist and musician whose practice centers on self-portraiture through the lens of gentrification, millennial issues, mental illness, racism, and sensory overload. Their images and musical performances tackle topics of gentrification, self-confidence, and the regularity of racial & sexual violence, while hypnotizing their audience with vibrant looping animations and catchy rhythms. RaFia also operates a fundraising initiative #PAYBLACKTiME that challenges people to individualize Reparations. They have raised $10,000 in food orders and various means of support for Black & Brown people across the United States.

It was a Sunday night, as it is now, when I wrote *that post*—my most-liked post on Instagram. Basically, a guy on a dating app felt the need to shit on my Sunday night by messaging me to let me know that he hadn’t read my bio before we matched and though he thought I was pretty, he wasn’t interested in me because I’m trans. I was mad. Why did he have to say anything, why couldn’t he have simply unmatched and let me live in trans peace? What annoyed me more was how he finished his message: “I don’t have anything against that, it’s just not for me. I hope I don’t sound ignorant!” Actually sir, you do! And if you feel the same, you do too. Let me tell you why. This man ruled me out for being trans, not because I have a dick. I know this because he didn’t bother to ask—for all he knew I could have had a glorious vagina! Nope, he ruled me out solely because I’m trans. If he had asked what I had in between my legs and I had told him and then he said he wasn’t interested I wouldn’t be upset. I respect that people have preferences on the sex of their partners. After all, I don’t tell my gay male friends they are misogynistic for not being attracted to women. For that man to say he doesn’t have an issue with transgender people is to imply he fully respects our gender identities, that trans women are women, trans men are men, and non-binary people are valid. In saying that he was attracted to me, but ultimately ruling me out simply because I am trans, shows that he obviously does have an issue with transgender people. Replace the word trans with a skin color, religion, ethnicity, or any other identity. Refusing to date a Jewish person because they are Jewish is anti-Semitic. Refusing to date a Black person because they are Black is racist. Refusing to date a trans person because they are trans is transphobic. How would you feel if your partner dated a trans person before you? If that is going to upset you or freak you out it is time to take a real look at your ally-ship and commit to doing better. You wouldn’t have a problem with them dating a cis girl before you right? Why should a trans girl be any different? That implies we are somehow less of a woman. People in the comments section kindly told me I was just pressed that I got turned down… For context, I’m not short on men, what I am short on however, is patience for buffoons who claim to accept trans people, while not accepting us in the same breath/message on a dating app. Listen, if you want to exclude yourself from the joy that is dating a person of trans experience, that’s fine. But if you’re going to be basic and ignorant, keep it to yourself, or at the very least own it sweetie.

Say no to transphobes, volunteer or donate to Mermaids UK (@mermaidsgender), protest for trans rights with Voices4 UK (@voices4ldn), and report violent incidents to the NYC Anti-Violence Project (@antiviolence), where you can train to combat violence in your community.

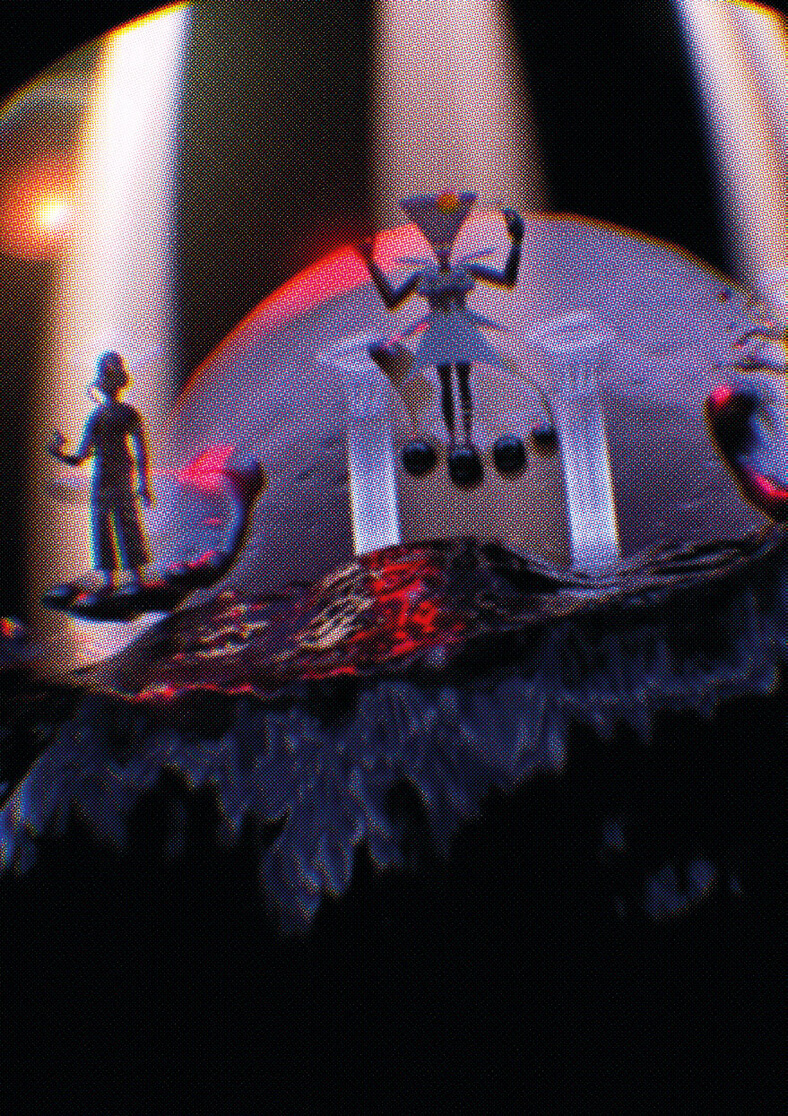

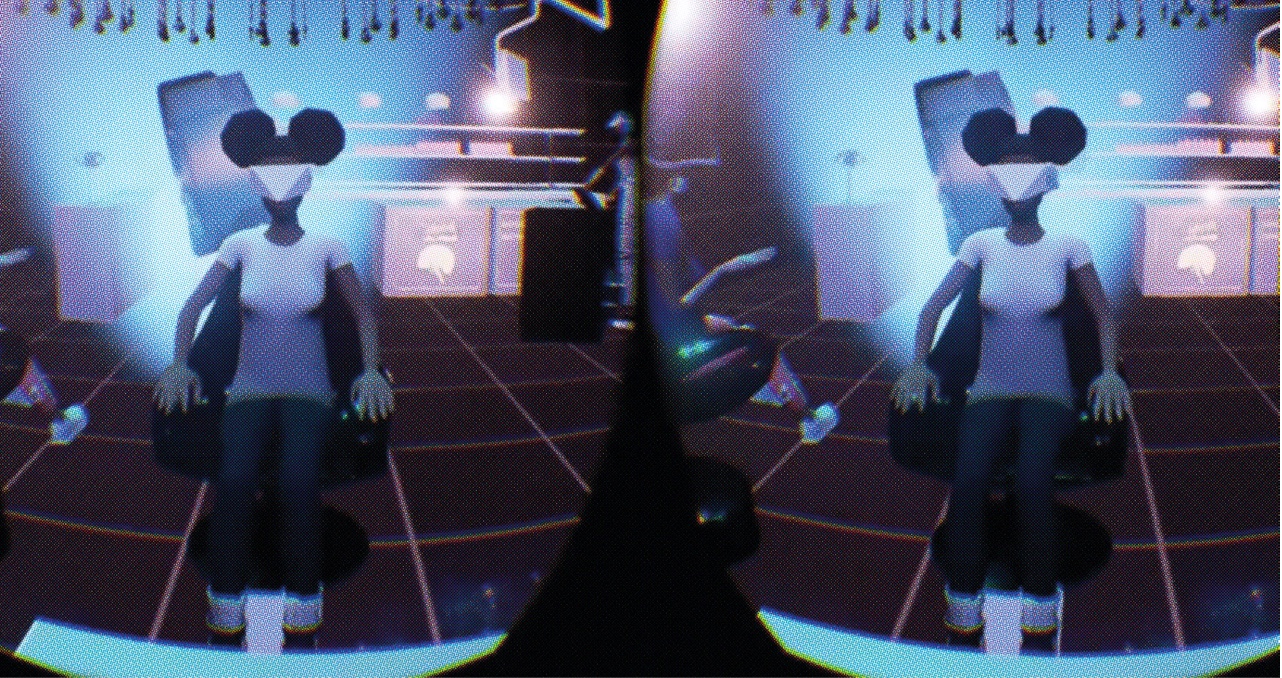

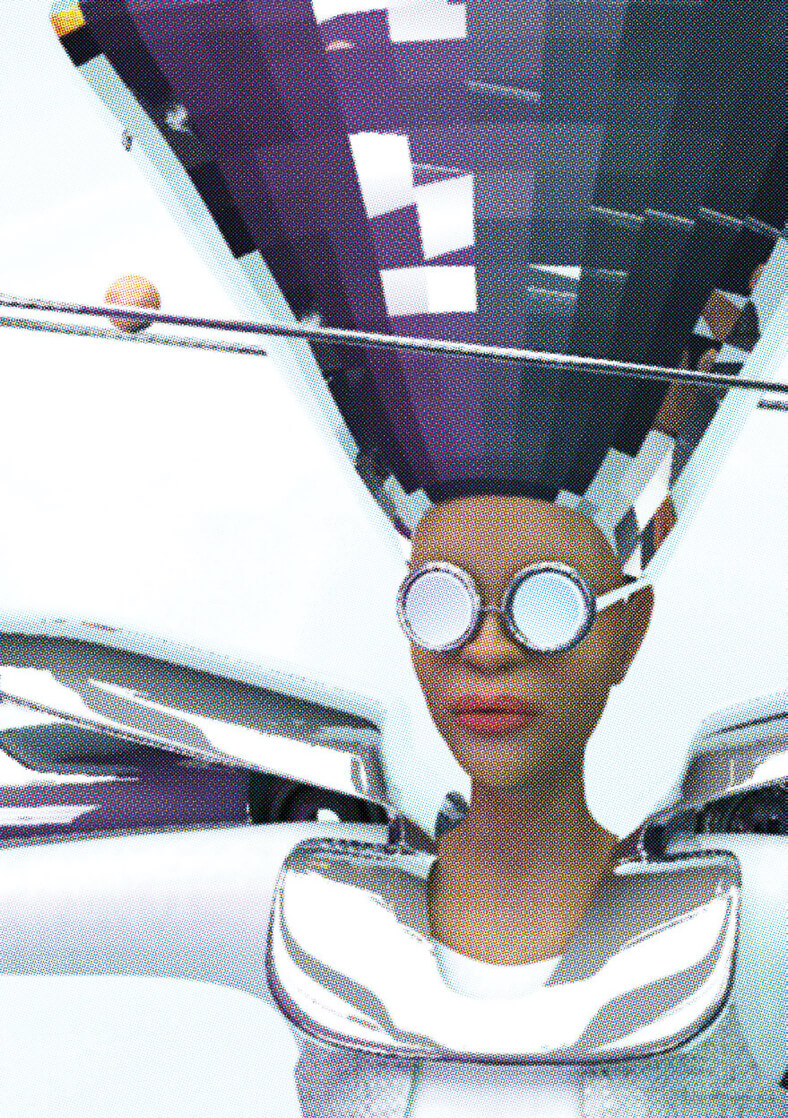

NeuroSpeculative AfroFeminism (NSAF), a three-part Afrofuturist narrative from Hyphen-Labs, an international art/tech collective of women of color, is an award-winning art installation and virtual reality simulation designed to counter the absence of Black women in product design, VR, and neuroscience. NSAF and Oculus Rift headset technology plant the viewer in the racialized body of the game’s avatar, Fatima, within a virtual world that imagines neurological optimization in the hands of Black women innovators, informed by culturally-specific rituals and experiences. In the final act of the project NSAF collects data from the viewer on the cognitive and psychological impact of viewing positive and empowering virtual images of women of color. Ash Baccus-Clark, a speculative neuroscientist and researcher with Hyphen-Labs, says the project was born out of a desire to see other Black women in science and technology. She, along with Hyphen-Labs co-founders and creative directors Carmen Aguilar y Wedge and Ece Tankal, worked with a global team of artists, engineers, and technologists to use emerging technology and design to help fill the gender gaps in her field. Their collective hope is that NSAF creates a space where women feel freed and inspired to make the virtual a reality.

I own a very large beaded medallion with the image of a woman in a traditional dress in red, and across the front, the letters “MMIW” in white beads. I wear this necklace to certain places and events specifically to have conversations about Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women. My decision to wear this medallion in white spaces, or non-Indigenous spaces, is to purposefully spark questions like, “What does MMIW mean?” and “What does your necklace stand for?”. I put it on with the intent to educate. I also remove it with the intent to set my own boundaries and with the knowledge that I am at my limit. Have you heard about this epidemic that affects Indigenous women in the United States and the First Nations of Canada? Have you heard that Native women are three and a half times more likely to be killed than white women?1 That two thirds of us will experience violence in our lifetime, and that one in three Native women will be raped?2 One in THREE. I know that statistic to be true whenever I gather with two of my sisters, because I am “one.” With this knowledge that Native women are at high risk for violence, sexual violence, and death, it is even more terrifying to know that NO ONE has exact figures for the number of Native women who are missing and murdered in the U.S. or Canada.3 The estimate in Canada alone is between 1,0004 to 4,0005 unaccounted for women since 1972. That’s a varying range of 3,000 women, and that kind of lack of data is unacceptable.

Are you outraged yet? Asking things like, “Where do they go? Who is taking them? Who is murdering them? Why Native women?”. The answers to those questions are not easy when data for the missing and murdered is so inconsistent. Many of our missing women are trafficked, oftentimes serving in the oil industry’s “man-camps” or other large urban areas where they are easily hidden.6 They are being taken by “boyfriends,” desperate family members, and men with colonizer complexes. They are being murdered by individuals who know that many Native women live in extreme levels of poverty. They’re being targeted because we as Native women are often overlooked by mainstream society. In 2013, it was discovered that Native women, children and babies were being trafficked across Lake Superior between Thunder Bay, Ontario and Duluth, Minnesota via large shipping containers on boats.7 Sex trafficking of our women, children and babies is a reality, and men are actively seeking to BUY our Native women and children. With the anger comes action, a plan, and tools I can utilize. What can I do with this anger so that it’s not sitting and festering inside me, but instead being used to create change? The first thing I turn to is medicines, our Sage, Sweetgrass, Tobacco, and Cedar. If I don’t ground myself in them or in other ceremony, the work I do to educate comes from a dark place instead of a place of healing. So what can non-Natives do? Use your connections, the privileges you have, the people you know, the networks you have access to, to lift up the Native voices who are already speaking loudly on this issue, so that their words are amplified. Use your money to support Native-organized educational material and buy artwork that brings attention to the epidemic. The more people who know about MMIW and are enraged by it, the more our women become seen. We have already been organizing against and resisting colonial violence for hundreds of years. MMIW is a systemic issue, one that stems from first contact and continues to this day—it is not something new to our communities. What is new, are the tools we have to stop it. From the breadth of information we have access to, to how we communicate it, we must all work together for our safety nation-wide.

To join the fight for the safety of Indigenous Women, follow: Sovereign Bodies Institute @sovereignbodies; The Buffalo Project @brothersleadingopenness; MMIWhoismissing @mmiwhoismissing; and Congresswoman Deb Haaland @deb4congressnm.

1 “Violence Against American Indian and Alaska Native Women.” Policy Research Center of the National Congress of American Indians. 2 “Full Report of the Prevalence, Incidence, and Consequences of Violence Against Women: Findings From the National Violence Against Women Survey.” U.S. Department of Justice. 3 “Reclaiming Power and Place: The Final Report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls.” National Inquiry Into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. 4 “Missing and Murdered Aboriginal Women: A National Operational Overview,” The Royal Canadian Mounted Police. 5 Walk 4 Justice Initiative. Native Women’s Association of Canada. 6 Martin, Nick. “The Connection Between Pipelines and Sexual Violence.” The New Republic. October 15, 2019. 7 “Garden of Truth: The Prostitution and Trafficking of Native Women in Minnesota.” Minnesota Indian Women’s Sexual Assault Coalition.

WHAT IS FEMALE GENITAL MUTILATION (FGM)? Female genital mutilation and cutting (FGM/C) is an extreme form of violence against women and girls, a human rights violation and a harmful practice that involves the removal of part or all of the female genitalia. It is most often carried out on girls between infancy and age 15, though adult women are also at risk. This form of abuse is carried out on every continent in the world, apart from Antarctica. FGM has zero health benefits and involves removing and damaging female genital tissue.

The World Health Organization has classified FGM into four categories: Clitoridectomy: partial or total removal of the clitoris and/or the prepuce; Excision: partial or total removal of the clitoris and the labia minora, with or without excision of the labia majora; Infibulation: the most extreme form, the removal of all external genitalia and the stitching together of the two sides of the vulva; Other: all other harmful procedures done to the female genitalia for nonmedical purposes, for example, pricking, piercing, incising, scraping and cauterizing.

FGM can have short and lifelong health consequences, including: Chronic infection/Hemorrhage/Complications during childbirth/Death/Increased risk of newborn deaths/Severe pain during urination, menstruation, and sexual intercourse/Psychological trauma.

The reasons underlying its practice are numerous and varied and ultimately serve to control women and girls’ sexuality. There are no religious texts that require FGM. The practice is often carried out by traditional circumcisers, who often play other central roles in communities, such as attending childbirths. However, according to a 2010 World Health Organization study of existing data, the medicalization of FGM is increasing. More than 18% of all girls and women who have been subjected to FGM had the procedure performed on them by a health-care provider; in some countries the rate is as high as 74%. FGM is a global issue. In 2016, UNICEF reported that over 200 million girls and women have undergone FGM, and 30 million are at risk over the next decade. In 2015, 193 countries agreed to include target 5.3 in the Sustainable Development Goals to eliminate FGM by 2030.

FGM AND CHILD MARRIAGE. In some contexts, girls undergo FGM to prepare them for marriage. In these communities, there is a social belief that un-cut girls make unsuitable wives. However, in certain regions, girls undergo FGM before the age of 5 but do not immediately marry, suggesting that there isn’t always a direct link between the two practices. Some communities might reject FGM but embrace child marriage and vice versa. The relationship varies from country to country and even within countries.

Evidence shows that the practice of FGM declines or stops when the human rights of women and girls are reinforced and legally protected, and a comprehensive eradication strategy is used. Such an approach fully engages families, community leaders, educators, lawmakers and enforcers, health care, child protection and social service providers to play an active role.

Call to action: FGM is a global issue that requires a global response. No matter where you are in the world you can help galvanize your government into taking FGM seriously, with the right funding and the right laws in place to end this human rights violation. Visit EqualityNow.org and search “Harmful practices” to find out how. @equalitynoworg

I was 13 years old when my father arranged my marriage. The man who was supposed to marry me was 29. I felt so bad because he was much older than me. I was scared because I know that if you get pregnant when you are young, you face a lot of problems with the delivery. My neighbor who had been married when she was young gave birth at home and did not get the help she needed, so she died. She was 15 years old. My wedding date was arranged and the bride price was negotiated. The man meant to be my husband had agreed to pay ten cows and four crates of beer. I felt bad because I am not a commodity to be exchanged. And when my father received the bride price my husband would then have the right to beat me or do whatever else he wanted to me. My father asked me if I wanted to get married and I said no, I wanted to continue with my education. My dream was to become a fashion designer. He said if I don’t want to marry that man, he would make me, with force. I was scared he would beat me, he was so angry. One reason I was scared is because I have not been cut. I knew that I was going to be cut because I could not marry without undergoing FGM (Female Genital Mutilation). I was scared because my friend and neighbor Njumal and her sister had been cut. It was organised as a ceremony, the whole community was invited. I went to see them being cut, there was a lot of blood and then they died. They were only twelve years old. There were three people holding my friends down. There are boys surrounding the group so that if the girl tries to run away, they can catch her and bring her back. When I saw her being cut I shouted stop it, but they carried on. I was crying. The women told my friend to stop crying because if you cry it brings shame on your family. After she died everyone left quietly, they said the man who cut her was not professional enough so they should find someone who is better. I was eleven years old. The night my bride price was negotiated I thought about all of these things. I went to bed, then at 6am I ran away from home. I just took my school books and I had no money so I had to beg a driver to help me. He took me to the bus station and the bus driver let me travel for free. I travelled to a secondary school in a village around an hour away. I stayed there for three months. My escape had worked - the wedding was called off! But eventually I had to go home because I had nowhere else to go. Once I was back, the village leader said my family should pay my school fees and other things. My father said that he did not have money to pay and that is why he wanted me to be married. After he refused, my teachers and friends provided books and pens. It was hard because I couldn’t pay school fees so the head teacher said I could not go to class or eat. I was allowed to stay at the school but not allowed to go to class or to eat, so the school matron would steal food for me. I felt very bad because I did not go to class, or have books or a pen. I didn’t feel like the other students. I felt like nobody cared. It went on like this for two months until the school holidays. Over the holidays my father beat me and only stopped when he said, “I no longer want her to talk to me, or speak to me about going back to school, she is no longer my daughter.” After the holidays NAFGEM came to my school. They educated the students about FGM and the teacher told NAFGEM my story and they started to help me. They have helped me by paying for my school fees and other things I need. They also gave me advice, they told me don’t be scared, we will provide you with what you need to go to school the way that other children get supported. Now I have finished secondary school and now I am at college studying tailoring and fashion. I learned to sew and am following my dream of being a fashion designer. I feel good when I design my own clothes. I want to become the biggest designer in the world. Now I’ve started making dresses, bags and other things to sell. If it wasn’t for NAFGEM, maybe I would be married with that man and would have three children. Every girl should have the chance to follow their dreams. When we #LetGirlsDream anything is possible and I am proof!

NAFGEM, the Network Against Female Genital Mutilation, is an association of individuals, groups, institutions, and other NGOs dedicated to ending female genital mutilation (FGM) and other harmful traditions towards women in Tanzania. Together with Equality Now, a non-government legal advocacy organization for the rights of women and girls globally, they are fighting to end child marriage and eradicate the practice of FGM.

Join the fight to end FGM and child marriage. Follow and donate to @NAFGEMTanzania and @equalitynoworg. Email and call government representatives to voice your opposition to FGM and your support of laws for the rights of women. Become a member of END FGM/C. Go to GirlsNotBrides.org and EqualityNow.org to read more testimonials from women like Ngalali, and learn how you can donate, support, and spread awareness.