Coming together to talk about activism, inclusivity and accessibility in an article published in the December issue of Vogue Greece, writer Elina Dimitriadi met with Jeremy O. Harris and Sinéad Burke. Both recently joined the Advisory Board of Chime for Change, the campaign that promotes gender equality founded by Gucci.

The new restrictions aimed at containing the pandemic have just begun to be implemented around Europe, everyone’s focus is on the U.S. elections and I am talking with two people who are striving for a world in which everyone is equal. Sinéad Burke is a teacher, activist and writer and through her company, Tilting Lens, she fights for fashion and a world that will be accessible to all. Jeremy O. Harris is an actor and playwriter whose work, Slave Play, was nominated for 12 Tony awards, the most Tony-nominated play in history. Recently, they both joined the Advisory Board of Chime for Change, a campaign that promotes gender equality, founded by Gucci.

My first question is where and how they quarantined and what followed was a flowing dialogue with two charismatic minds that have spotted the cracks in an antiquated system and are looking for solutions that involve tearing everything down and building something new, more encompassing and therefore more resilient, rather than fixing those cracks.

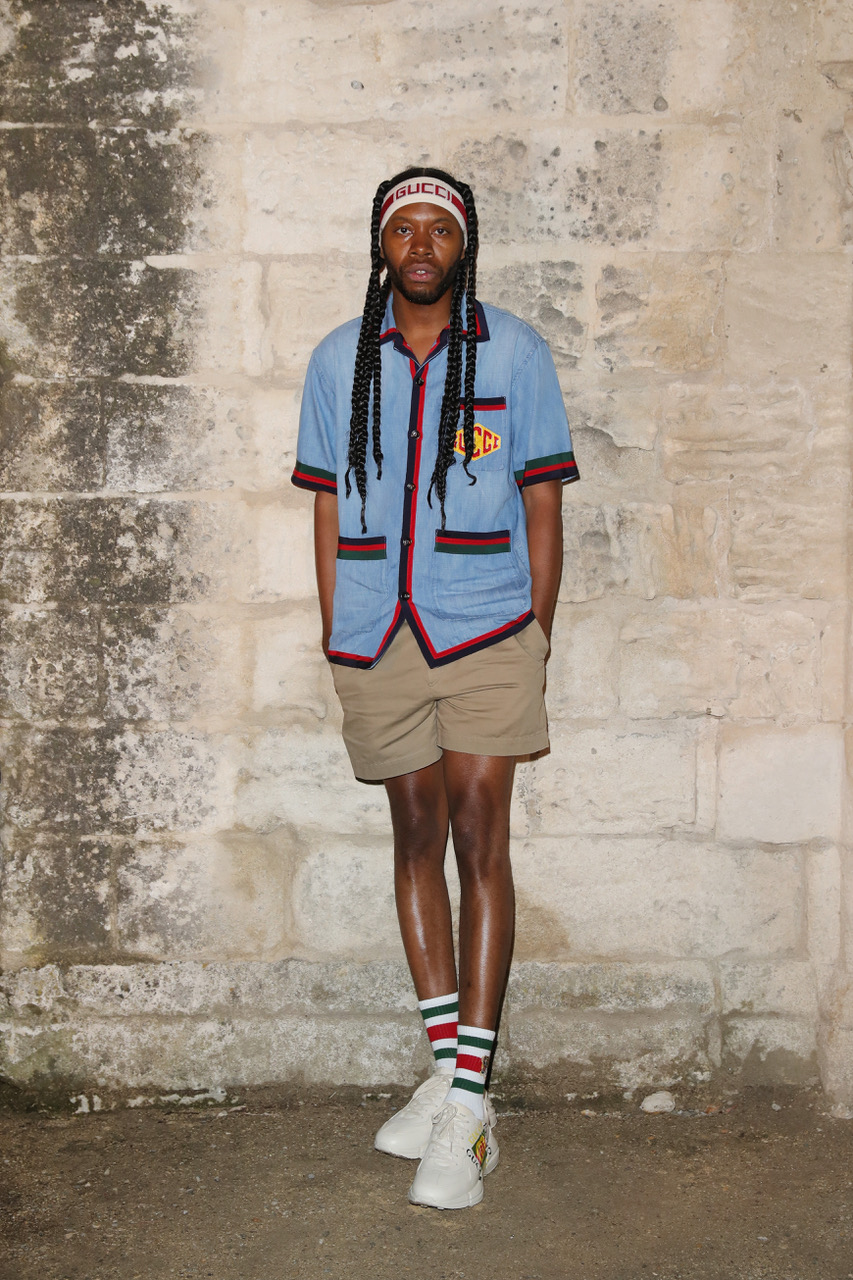

Jeremy is answering from Rome where his is writing his new play and also participated in the video directed by Gus Van Sant, presenting the new Gucci Collection by visionary Alessandro Michele. “I was glued to the TV for 20 hours a day, watching the US elections. My mind must have been more active over the last few months. From the first lockdown eight months ago, I had decided that I would spend my time taking care of myself, because the psychological shifts came in rapid succession. So, I made pleasure my sole guide. If I wanted to watch anime for six consecutive hours or eat burgers, that’s what I did. If I wanted to read a James Baldwin book, I read it. I did not pressure myself to create. It takes effort to get rid of this pressure. Also artists have to heed this constant, fretful pull to create something in difficult times, with Shakespeare almost always being the example, since he wrote King Lear while quarantined due to the plague. Well, I think that young artists who are anxious to write the masterpiece about Trump or Covid-19 might be relieved to hear that Shakespeare’s masterpiece after the plague was a family complot with elements of a soap opera which, in our day, would be aired on Sunday night TV. Something like the series Succession, but a tad sexier,” he says and we burst out laughing. Being black and queer in America, I need to keep reminding myself that I do nave to keep on writing about the oppression I went through to feel that my work is valuable,” he says.

Sinéad says she had a somewhat different lockdown experience. “I returned to my family home in Ireland and when I realized that I would have so much time on my hands for the first time, I decided to do things I had been wanting to do for some time. One of them was to write a children’s book. I made good use of my experience as a woman with a disability and an elementary school teacher, I wrote for the kids who don’t get to hear “you’re valuable just as you are” often enough. I do not feel disabled due to my medical condition, but because of the way the world is designed. We should not have to be the ones to change so that we fit in or feel that we have worth. And children need to feel that they have the tools and the skills to make the world a safe place for all.”

“I am obsessed with the idea of finding new frameworks in which to discuss issues like disability or what’s important at this given time. One of my favorite teachers is in a wheelchair. She has taught at Yale, Harvard and MIT, but none allowed her to teach remotely, when her body required her not to move. Now though, we are all working from home and it’s as if we are all disabled. And, just like that, universities saw that remote learning works,” Jeremy adds.

“But it was never impossible, there was just no inclination to facilitate the lives of those who experienced difficulty. So, as we move into the next phase, it’s important not to rush to rebuild our economies and societies while still treating disabled people as a vulnerable group. We should not say to them “you go on and stay at home, where you are more comfortable, while we go out and rebuild the world.” We have done this in the past, we dealt with them as problems and we institutionalized them. When we redesign life and the spaces we live in, based on social distancing for example, we can work with disabled people so that they can give us their input on how they can best be served as well. So that we design a world that is accessible to all, with equal opportunities, that will endure longer and be more viable,” Sinéad continues in a peaceful but forceful tone.

“I think we need to take advantage of this pause to change our conscience,” Jeremy believes. “Contemplate contexts designed to include everyone. For example, no fashion house staged a large show with the public present, as is usual. So this is a great opportunity for imagining how the environment can be expanded, how the front row can be configured, who can be invited or see the clothes worn by him or her.”

“The solution is not to place the under-represented communities on a temporary pedestal, but to have available all the platforms through which to be heard,” says Sinéad. “It’s nice to be able to see diversity more, but what is the next step? Profit by selling the aesthetics of these people or develop relationships with these communities and design educational and professional opportunities and venues so that they can participate at all levels? I was the first little person to be on the cover of Vogue. The first one to be invited to the Met Gala. I am grateful that a 12-year-old child with my disability can see that something like this is possible. But for progress to happen, I cannot be the exception. As Kamal Harris said, I may be the first but I do not want to be the last. We are trying to transform established systems which is a big challenge that takes time, but it is time for it to be done.”

“The solution is to hire more people in key roles, not just put them on magazine covers. When I visit companies that want to make a movie out of one of my works or produce one of my plays, I always observe their offices to see whether people like me work there – young, black, queer. If you do not know how to incorporate more people, give them a voice or satisfy their needs, then the solution is to hire one of them to advise you. This is why I am thrilled with our role at Chime for Change. This is the first time I will sit at the same table with a CEO, an activist and a pop star. And we will participate in discussions about what such platforms can offer people who have been overlooked historically or who fashion addresses in the final analysis.”

I feel that the Chime for Change meeting room is like a song from the musical Hamilton- The room where it happens (the place where the important decisions will be made). “Exactly, and that these initiatives to promote equality by a popular brand like Gucci can overcome geographical and linguistic barriers, is an optimistic note,” says Sinéad. “I often tell designers when they have to prepare an outfit for me. My body has different needs and someone with my disability could help them adapt their design and techniques. I had no options growing up and my father, who has the same disability as me, treated fashion in a utilitarian way. However, fashion would become the tool through which I could control my own aesthetic. This is something I always wanted, because people would make assumptions about who I was or what I could accomplish, based on my appearance. Fashion gives me the power to write my own story, how I have decided to present myself to the world, whether it be wearing sweats at home or a cape to go to the supermarket. Also, we need to acknowledge that clothes touch our skin, we have an emotional relationship with them, they are part of our being human. Some people may have walked around their home naked during the lockdown, but in most countries we have to be dressed,” she continues undaunted. “So the fashion industry is one of the few industries with which we almost all have an essential relationship with. And an industry that affects everyone should design a system that will address everyone, through a prism of equality, sustainability, creativity, innovation and profit.”

“Clothes are one of the first stories that people can read on us. As a black person, I ponder how much my dark skin complicates this story. And the complex understanding of the black body was always constructed on the basis of the clothes, whether we felt that our appearance needed to make us feel safe in respect of the class that oppressed us or when we wanted to warn our oppressors. This is precisely why I believe that fashion and the theatre should be more closely related. Theatricality should be part of a fashion show and small theatrical communities can benefit from the impact that fashion has on the world to promote the issues that are important to them,” Jeremy believes.

My last question sounds like a song, Sinéad tells me. So, what gives them the optimism and faith that they will be able to build the world they have in their minds? Jeremy believes it is TikTok. “That is where I am surrounded by young people, their humor, rage and passions, I learn what they consider beautiful, what they believe is ugly and feel the energy of connecting with them at a time of intense loneliness. I think that my 17-year old self, that felt so lonely in Virginia where I grew up, would have felt wonderful if he had TikTok. I’m happy that my presence there can make 11 year-old kids that dream of becoming like me believe that they can make it.”

For her part, Sinéad says “I am thrilled that through these platforms and young people can create content and stories that are not necessarily related to their identity, so they can simply express their artistic interests. It is also important that, for example, Jeremy helps young people experiment with internet shows like Circle Jerk. Minorities were always under pressure to achieve perfection whenever they were given the opportunity to create, because they would have no second chance. We need to financially support young people to explore their curiosity, try, fail.”

“We are living through a situation much like the one that occurred one hundred years ago. A pandemic coupled with the rise of the far right globally. If we do not want to back track, this is the time to shake up the system so we can move forward, “ says Jeremy. “Recognize the trauma and the decisions that led to the systemic barriers and oppression, so that those who lived through it can be heard, feel that they are understood and build the future together,” Sinéad concludes.

Listen to Sinéad Burke and Jeremy O. Harris in conversation with Vogue Greece editor Elina Dimitriadi in an episode of the Gucci Podcast.